One Shot: Ten Years After

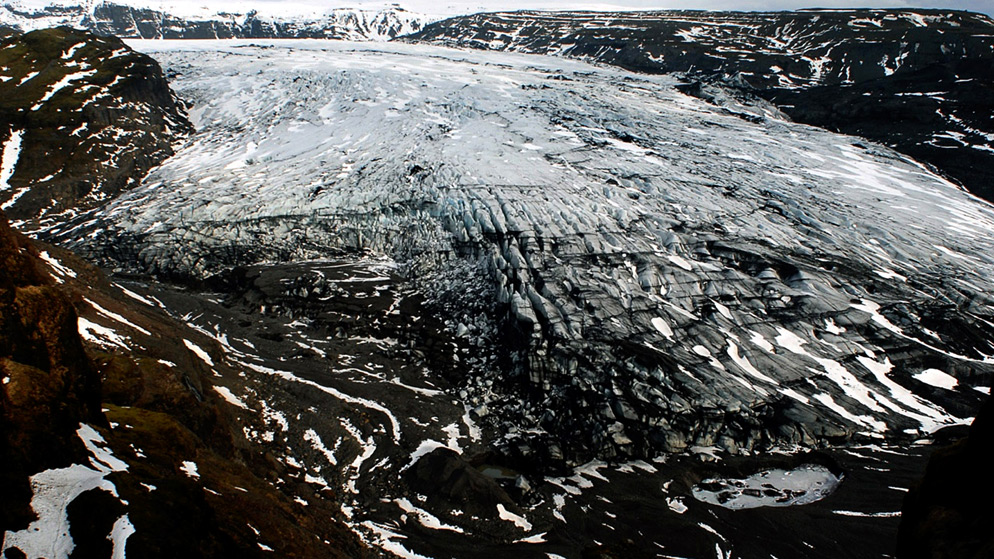

The Sólheimajökull Glacier in 2007, the year the Extreme Ice Survey began. D200, AF NIKKOR 20mm f/2.8D, 1/350 second, f/8, ISO 200, aperture priority, Matrix metering.

The Sólheimajökull Glacier in 2016, from the same camera position. It's been reported that Iceland is one of the fastest warming places on earth. D3200, AF NIKKOR 20mm f/2.8D, 1/800 second, f/8, ISO 200, aperture priority, Matrix metering.

We've all seen images like these, images that are the photographic evidence of changes taking place over time. These particular photos were made by remote cameras on the Sólheimajökull Glacier in Iceland, the first in 2007, the second in 2016.

The photographs mark the tenth anniversary of glacier monitoring by James Balog, his associates and their project, the Extreme Ice Survey (EIS).

At the start, in 2007, there were 25 Nikon cameras—D200s and D300s—in time-lapse rigs on glaciers around the world, placed to document one of the effects of global warming. Today there are 43 cameras—D5300s and D3200s, for the most part—at 24 sites.

The years have revealed, in Jim's words, "the most tangible, immediate concrete evidence of climate change that exists today."

The landscapes we're recording are going to be gone. I pull out the flash card, and I realize the memory of that landscape exists only on that card. I'm holding in my hand the evidence of its existence.

The story began for Jim in 2005 with an assignment from The New Yorker to photograph a melting glacier. That assignment, and the fact that Sólheimajökull had receded almost half a mile in less than ten years, led to Jim's photography of glaciers in Alaska, Montana, Greenland, Iceland and Bolivia, and, ultimately, the cover story, The Big Melt, in the June, 2007, issue of National Geographic.

Along with the 25 original cameras that took the pictures for that story were battery packs, voltage regulators, intervalometers, light sensors and solar panels. The cameras were able to shoot during daylight hours for eight months, then switch to two- or five-frames-per-day for the short months of the year. When the EIS crew checked the cameras, the memory cards were pulled and replaced.

The images captured were of disappearing landscapes. "The landscapes we're recording are going to be gone," Jim said at the time. "I pull out the flash card, and I realize the memory of that landscape exists only on that card. I'm holding in my hand the evidence of its existence."

EIS's work has led to exhibits, presentations, an Emmy-award winning film, Chasing Ice, and a book, Ice: Portraits of Vanishing Glaciers. During the years of EIS activity Jim has served as a U.S./NASA representative to the 2009 United Nations Conference on Climate Change and has given presentations on the project at a TED talk, at the White House and the Environmental Protection Agency. He is currently working on a new film that's scheduled to be released in the first quarter of 2018. The working title is The Human Element. "We're taking the EIS story and looking at sea level rise that comes from the ice," he says. "The story of global change starts with air—if you change the air, ice melts; if ice melts, the water rises. If you change the air in many areas, droughts happen, and if you have drought, forests dry out, and then burn."

In ten years of working with and among scientists, photographers, engineers, researchers and technicians, he's found that "science and the collection of objective information has been prescient. What's happening and where we're going was and is perfectly predictable and comprehensible."

There are no simple solutions to what we face in the future. "A large number of actions need to happen," Jim says. "The hopeful aspect is that there is sufficient knowledge to understand [what's occurring]. We can alter the course of history, but it's now urgent—a whole lot more delay and we're over the cliff. The only hope is to stay optimistic and do what needs to be done to support the efforts of science and those who are documenting those efforts and the changes that are taking place."