Relax, He's Friendly: How a Determined Photographer Made the Photo of a Lifetime

Antonio Pastrana used two Jaunt D80F 8000-lumens LED professional video lights, one on each side of his Ikelite housing, to make this startling photo. "The important thing was to have the lights on from the moment I went into the water so the crocodile would be acclimated to them and not get scared when I turned them on." The picture has won several awards, including one in the 2019 World Photographic Cup competition. D850, AF-S NIKKOR 14-24mm f/2.8G ED, 1/250 second, f/6.3, ISO 500, shutter priority, Center-weighted metering.

"It was a little bit of a tango dance," Antonio Pastrana says of the maneuvers made prior to the taking of this photo of the crocodile known as El Niño.

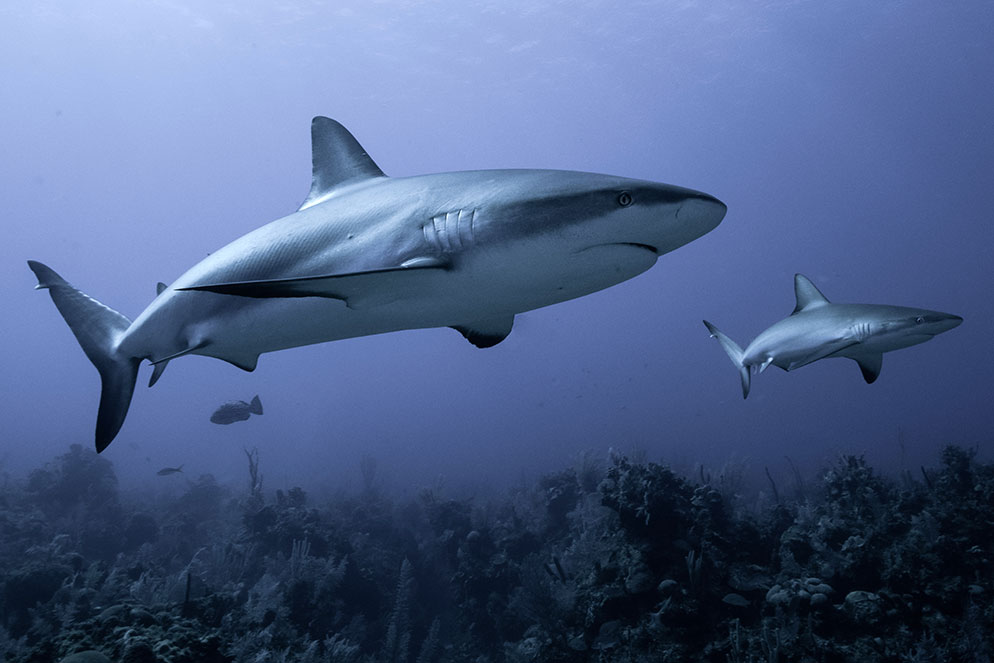

Antonio and two other snorkelers had been watching El Niño for two hours from a small boat at the Gardens of the Queen, a marine park off the coast of Cuba that's home to coral reefs, mangroves, fish, sharks...and crocodiles.

"He was relaxed," Antonio says. "We threw him a piece of chicken and he didn't eat it, so we decided he was fed, but still, the moment before you go into the water—let's say it's worrisome. Your brain calls you back, tells you you're crazy, but you go anyway."

El Niño is well-known to park officials and divers and photographers who pay repeat visits to the Gardens. "He's a Morelet's crocodile," Antonio says, "so he's not so big—his body is about one-and-a-half meters [about five feet] and his tail another meter [about three feet], but he has a lot of teeth."

Well, yes—there is that. All those teeth.

But Antonio had been told that El Niño is used to people and curious about them and almost eager to approach them. Words like "friendly" and "nice" were used to describe him. "Maybe that just means he hasn't eaten anybody yet," Antonio says.

Still, he and his companions go into the water, and the dance begins.

"At first, I approach him," Antonio explains. "Then he approaches me. We're slowly getting closer until he's maybe five meters [about 16 feet] from me, but now we're in the shallow area and his feet are in the marshes [of the mangroves], and if he wants to, he can run away."

Antonio wore scuba gear for this photo taken in the pristine, protected Gardens of the Queen marine park. "There is so much to photograph—coral, sharks, fish, crocodiles." D850, AF-S NIKKOR 14-24mm f/2.8G ED, 1/320 second, f/20, ISO 1600, manual exposure, Center-weighted metering.

Antonio is there to get not just any picture, but the picture of a lifetime, so he definitely doesn't want El Niño running away. As his companions move to either side of El Niño, the crocodile begins to swim slowly toward Antonio. "I back up into deeper water and he's keeping up with me. I have to stay on his nose—crocodiles attack to the side—and I have to keep the camera's housing between us. He's 30 centimeters [about a foot] from the dome of the housing when he starts to circle. I move to keep on his nose. If he throws a bite, he gets the dome, and if that happens I'm out of the water and back into the boat."

But El Niño doesn't attack. "He goes down into the deeper water, and I take a deep breath and go down with him—I've got to keep him in sight—and that's when I take the picture. Then he goes even deeper, swimming under me, and I'm losing air." Antonio takes a few quick pictures, then heads for the surface and the safety of the boat.

And that's when he makes a mistake.

Seeing that he's made the photograph he hoped for, he calls his wife, Ana, on his satellite phone. "I say, 'I just took the shot of my life,' and I send it to her phone. She sees it and screams at me, 'You're crazy!' and I say, 'It's okay, I took it with the telephoto lens,' and she says, 'I know your housing, and it doesn't fit a telephoto!' And of course she's right. I took the shot with a 14-24mm."

Busted. But safe in the boat, with the photo of a lifetime.

By the Book

Antonio Pastrana doesn't wait for opportunities to come his way. He makes his own. A nature photographer based in Mexico City, he developed his twin passions for photography and nature at an early age, took a photo course in school and after graduation worked as communications director at the Parque Zoologico de Chapultepec in Mexico City. "At that time, the zoo had its 80th anniversary coming up," he says, "and I had an idea."

Antonio's family's business was magazine publishing, and his idea was to do a book on the zoo. "I decided the city should have a book about the zoo to mark its anniversary, and doing a magazine and doing a book—how different could it be? Pages and stories, right?"

He knew the zoo would be ideal for photography—the animals live in exhibits, not cages—and Antonio, who saw his role as publisher, not photographer, contacted local nature photographers he wanted to hire, to do the job. "I never considered doing the photography—until they told me their fees," he says. "I didn't have that kind of budget, so I decided to do the photography myself. And I did—I had a great time, we printed five thousand copies and the book was a great success. Some big companies in Mexico were the sponsors, and they were very happy."

Not long after, Antonio was contacted by a university director who said he loved the zoo book and wanted a book produced for his university. For that volume Antonio tied in a nature theme and got a noted Mexican anthropologist and historian to write the text.

"This is my Kermit the Frog, photographed in Chiapas, Mexico. These red-eyed tree frogs are indicator species—when you see this frog, it means the eco system is healthy." D810, AF Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8D, 1/160 second, f/16, ISO 3200, manual exposure, Center-weighted metering.

Before long Antonio became the go-to photographer for industrial and corporate assignments as well as projects for government agencies. So far he's published 35 books, and nature is always a part of the story—sometimes literally, sometimes symbolically. "There is a nature ingredient in everything," he says, "and I talk to companies about the importance of putting nature in their core businesses and communications. That's the way I work. I sell the client an idea, and I get hired."

Sounds like a perfect plan: pitch concepts, create opportunities, take pictures. Crocodiles optional.

Sunset in the mangrove area of the Gardens of the Queen where Antonio photographed El Niño. D850, AF Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8D, 1/200 second, f/22, ISO 250, shutter priority, Center-weighted metering.