Tips for Shooting Sports

Sports shooter Bill Sallaz knows what he wants and where to stand in order to get it

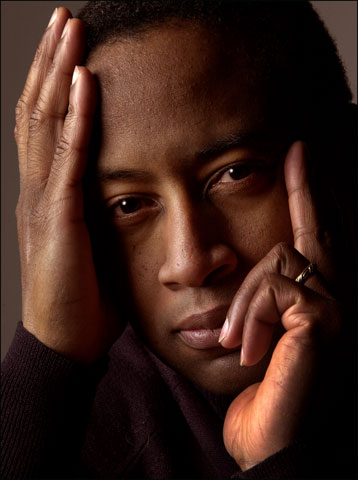

Bill Sallaz is a Nikon Legend Behind the Lens.

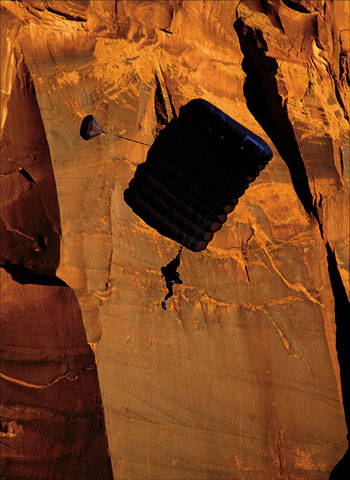

One of the first things he mentioned to us years ago when we first interviewed him was geometry. William R. Sallaz told us he saw the geometry of a scene—its lines and shapes—before he saw the color, texture or even the emotional content. He said it had to do with his education—he studied engineering in school—and his early career as a draftsman. Next he looked at the light: "I'm drawn to dramatic light. I like to shoot back-lit or side-lit. I'd be happy making pretty pictures of nothing as long as they had strong geometry and dramatic lighting." For 30 years Bill's advertising, commercial and editorial photographs have featured shape and light as signature elements of the images he's made for major international companies and ad agencies as well as magazines like Sports Illustrated, Time, Newsweek and People.

He doesn't classify himself as anything other than a generalist. "I lived in Montana for a decade," he says, "and when you live in a state where cows outnumber people six to one, you learn to shoot a little bit of everything. I ran a studio up there and also did commercial photography, shot portraits [and events], shot for local colleges and covered news and sports for AP as a stringer." There's no denying, though, that sports have been his specialty, from auto racing to baseball, tennis to fencing, football (he's covered four Super Bowls) to the mixed bag that six Olympics offered up.

He doesn't claim equal familiarity with all sports—and that can be a plus. When you photograph a sport you're not that familiar with, he told us, you'll probably look at it with a fresh eye. "A photographer who shoots that sport week in and week out has kind of locked himself into doing the same pictures over and over, so coming to the sport fresh is a good thing." Familiar or not, you have to come to the event armed: "I'm not really a fan of auto racing, but I've paid enough attention to...know who the top ten people in [the] sport are. If you haven't got any understanding of the sport and haven't done any research, you're not going to be able to take advantage of, say, the veteran driver talking to the rookie. Chances are you won't even recognize them."

What he learned in one field, he often applies in another. "I've always told people that being a portrait photographer made me a better sports photographer, and vice versa. With a hinky portrait subject you might get one opportunity to tweak a real smile, and if you're not ready to jump all over that moment, you'll miss the shot. Sports photography made me better at portraits because I was quick and observant. On the other side, by controlling the light and the setup for a portrait, I could walk into a sports stadium, look around and decide where I wanted to be in relation to the angle of the light and what backgrounds I wanted to shoot into." No matter the subject or the assignment, Bill always has a clear idea of what he wants. "I previsualize things very well, and I have a pretty good sense of how everything's going to look in the photograph. I'm seldom surprised."

I've always told people that being a portrait photographer made me a better sports photographer, and vice versa.

Recently, it's been some of his newer clients who've been surprised. A few years ago Bill began thinking about cutting down on his traveling. "I was looking for a way to turn my skills toward something closer to home," he says. When an invitation came to photograph a semi-pro football league in his home state of Colorado, he took the job. "When the photos went to a website there was a substantial response," Bill says. "I figured, why not try it on a high-school level?" Soon a business—ActionPic9, devoted to the photography of youth sports and local sports events—was born. "It turned out to be a way to do what I loved doing—sports—and stay local," Bill says. "The work involves the same skills and the same discipline. Regardless of the client or the market, it's about capturing the key moments and the overall ballet of the sport itself. That doesn't change.

"It's working out very well, and now, on a Saturday morning, I'm not in an airport somewhere; I'm out on my bike, riding with friends and family."

The surprise comes when the clients for the new business see the results. "I got comments on how great my hockey photographs were. Someone said, 'Wow, you can see the puck in every picture.' And then he asked, 'What kind of camera are you using?'"

Well, the camera probably helped, but in Bill's hockey photographs the puck stops here because the man behind the camera has 30 years of photography experience. And he knows geometry.

From the Vault

If you're into sports photography, we want to pass along some of Bill's thoughts about improving images.

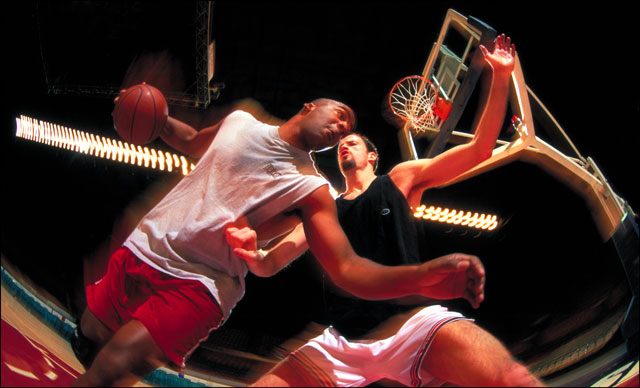

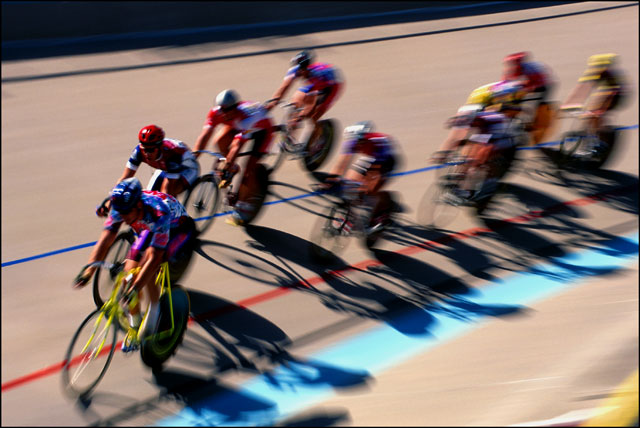

In general, don't chase the picture all over the field. "Put yourself in the best position you can and wait until the action comes to you." In fact, wait until the action comes uncomfortably close—in the telephoto lens, that is. "The action should be so close that you're cutting off arms and legs in the frame," Bill says. "Shoot tight and you'll find there's greater visual impact. Try not to get a lot of sky and grass—that's not what the sport is.

"Here's how to practice: If you're used to shooting baseball with an 80-200mm zoom, commit to shooting it with a 300mm telephoto for the game, or use a tele-extender on your 80-200. Max out the lens to its tele end, even if you miss pictures because you cut off body parts. As an exercise it's like swinging a weighted bat."

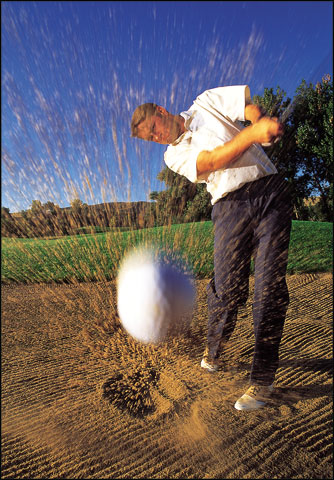

Bill also suggests practice shooting. "If you've got a game at three o'clock that's important to you, go out and shoot the one o'clock game for practice. Shooting pictures is like playing a musical instrument; you can't play once a week and expect to make great music. When I was learning this craft, I used to shoot high-school football games without film in the camera on Friday nights and then really shoot the college game on Saturday and the pro game on Sunday. The high-school game was to get into the rhythm and to get used to what I'd be seeing."