The Power and Beauty of Bears and Other Animals

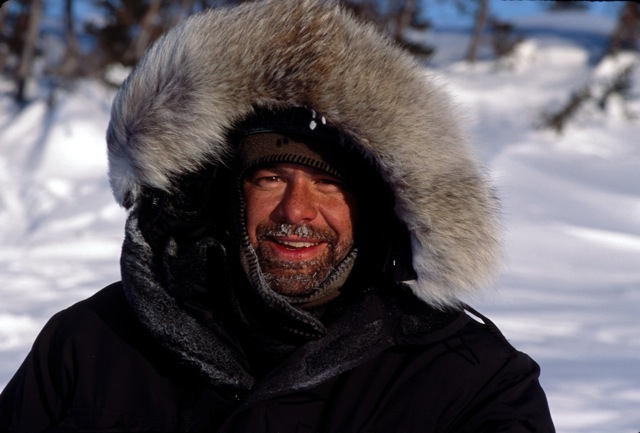

Daniel J. Cox is a Nikon Legend Behind the Lens

If it hadn't been for the bear in the backyard, things might have been different for Daniel J. Cox.

As a teenager growing up in the tiny northern Minnesota town of Twig, Dan took notice of the black bear that liked to wander through the family's yard every so often. "We lived in farm country at the edge of the wilderness," Dan says, "so we saw a lot of animals. At first the bear was a little scary, but we got used to him and he to us. After a while I realized I could photograph this guy."

Bears became an ongoing "life's work" as Dan became one of this country's leading nature photographers. In his book, Bear: A Celebration of Power and Beauty, his photographs combine with text by Rebecca L. Grambo to create a fascinating study of the natural history of the bear, as well as a look at the creature's role in myth, legend and folklore.

Photographing bears in the wild, Dan will tell you, is not something you do without lots of preparation. They are dangerous subjects, and some are a lot more dangerous than other animals.

"You have to take precautions and have respect for all bears, but, in general, black bears are less of a problem to photograph in terms of threat or danger," Dan says. "They're much less aggressive and more predictable than grizzlies or polar bears."

Essentially what you're looking for are...well, contented bears. Meaning, well fed ones.

"I'd say that 99 percent of my work with grizzlies is done in Alaska, along the streams where salmon provide the bears with a tremendous food source. I've worked in the interior of Canada and Montana, and I have a few images of grizzly bears in Yellowstone, but I don't feel comfortable for the animal or myself when I'm working in those areas. The animals there are so highly stressed from trying to find food. They just don't have the food sources that Alaskan bears do, and because of that they're grumpy."

Not that bears will view humans as a food source. Generally a bear will attack only if surprised or if it's guarding a food cache or protecting cubs. But, as Dan says, bears are very sensitive to smells, and they're very curious. "If you're camping and a bear smells anything—could be soap, toothpaste, hair spray—he might come around to check you out.

So being a smart as well as a skilled photographer, Dan would rather photograph bears such as those on the salmon streams in Alaska that are "fat and happy and don't feel threatened."

I got into this work because I love being in the outdoors, and I love photography. Equally strong is my interest in natural history and wildlife and my concern about our environment. I want my photos to be used in a way that's consistent with my feelings about the animals I photograph.

Polar bears are a different story. There isn't all that much choice of territory, and they can be a bit on the testy side. Dan likes to photograph them in northern Manitoba, Canada, and he does it from a tundra buggy—a large, secure and very stable vehicle that's a safe haven for people who want to view the bears.

"In the fall the polar bears congregate on the shores of Hudson Bay, waiting to get back out onto the ice. Seals are their main food source, and they have to get out onto the ice to hunt. They lose the ice by mid-July each year, and they're land-based for several months without food, basically in walking hibernation until the ice forms and is solid enough to hold them, which usually happens in mid-November."

Dan has never been on the ground with a polar bear. "You don't want to be, ever, but especially when they've been without food for several months. I've seen people on the ground with them, and those bears are looking at them pretty seriously."

Shooting from the tundra buggy, Dan likes to use very long lenses. "You're ten or twelve feet off the ground in one of those vehicles, and if you shoot with, say, an 80-200mm zoom, the picture is going to look like you took it looking down on the bear from a helicopter. I shoot with a 500mm lens to cut down the angle and make it look like I'm a lot closer to the ground. The long lens gives the photo a much more intimate feeling." Most of the time he'll shoot through a rolled-down window and stabilize the lens by resting it on a beanbag.

Not every creature is as difficult to photograph as a bear, of course, but the common denominators are knowledge and respect: know the habits of the animals you want to photograph, and respect the animal's freedom and preserve its safety.

"I got into this work because I love being in the outdoors, and I love photography," Dan has said. "Equally strong is my interest in natural history and wildlife and my concern about our environment. I want my photos to be used in a way that's consistent with my feelings about the animals I photograph." To that end he works with several organizations that have the need for the kind of photographs he takes, but not necessarily the financial resources to obtain them. "I feel that's part of the give and take of what I do, and it's rewarding for me to be able to make a contribution to a cause I believe in, using my talents as a photographer."

Start Small

We realize that bears in the wild—and, for that matter, many of the other creatures Dan photographs—may be beyond your reach. But Dan has other subjects, ones we can all photograph.

"One of the things I enjoy a whole lot and do for personal satisfaction is photographing birds right in my own backyard," he says. "It's just a matter of getting a good feeder, putting the food out for them and being ready with a long telephoto and a sturdy tripod."

Dan recommends a focal length of at least 300mm—"because the birds are so small"—and suggests that you place the feeder where there's a pleasing background for your photos. If you're serious about this, you can even do a little landscaping to provide a photogenic setting.

"Birds are consistent," he says. "Once they know the feeder is there, they'll come in from the same direction and use the same tree branches, almost like a landing site."

Daniel J. Cox has been an NPS member since 1984.