The Importance of Composition When Shooting Nature

Pat O’Hara is a Nikon Legend Behind the Lens

Pat O'Hara had to go far from home to really appreciate the surroundings of his boyhood. True, his first interest in nature came from those surroundings—as he says, "one of the most influential factors in my life was that I was born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, in the midst of mountains and national parks and forests"—but it wasn't until he was half a world away from that environment that he realized how important it was to him. "I was in Vietnam in the late 1960s, at the Air Force base at Cam Ranh Bay," Pat says, "and my roommate, who was from Kansas, received care packages from home every month, and inside the packages were nature magazines. His parents were active naturalists, so he was getting National Wildlife and Audubon, and I looked at the photos in those magazines and I just escaped into them."

He doesn't underestimate the importance of those photographs. "Here I was in a war zone, and I was looking forward to my roommate's packages because these magazines had these lovely photographs, and it was an escape for me. I just started dreaming about being out of the military and having some kind of profession relating to nature. And, of course, at the time the photography was so impressive to me."

So he bought a camera and began taking pictures while on R&R. "It was a basic rangefinder, but I started photographing pretty seriously in terms of composition." Later Pat was assigned to Korea, where he was able to use the darkroom facilities at an Army base adjacent to his Air Force post. "That's when I really got into photographing. It was all black and white then, and I'd take the pictures and process the film myself. That was the aesthetic starting point for me."

Today Pat is one of the leading environmental nature photographers in the world. His photographs have been featured in over a dozen books, in countless magazine articles and on calendars and posters. Among his numerous awards is the New York Art Directors Club Photography Gold Medal and Communication Arts magazine's Award of Excellence.

Throughout his career, a constant has been the precision of his composition. "Precise composition has always been a goal of mine," he says, adding with a laugh, "It's probably one of the few areas of my life where I have any precision." To achieve this goal, Pat takes special care to make all the pictorial elements fit together, "so the pictures don't appear to be too busy, which can be tough when I'm working with a wide-angle lens."

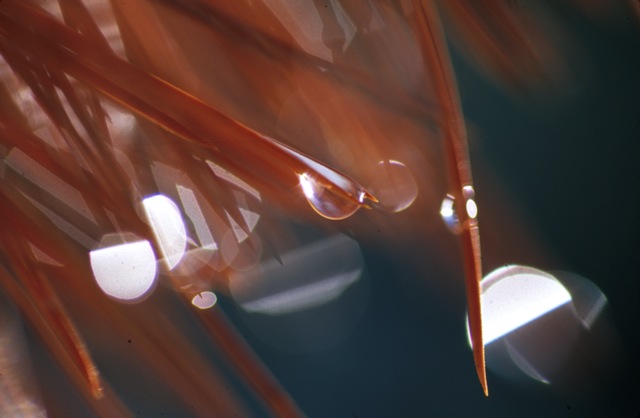

But for Pat, precise composition means more than just noticing the general structure of a landscape. It’s about paying attention to the particulars in a scene. Choosing the right lens was an important part of helping him cultivate this skill. “The first lens I got was a 55mm macro, and it was a good choice, especially for someone starting out. Not only did it allow me to do both close-ups and scenics, but it directed me to pay attention to a lot of details."

After the military, Pat attended college. "My interest was environmental education and natural history," he says, "and my goal was to eventually go to work for the National Park Service in a division that used photography."

Things didn't turn out that way, and perhaps that's for the best. "I think I would have eventually been promoted into a desk job if I'd gone for a park-service career, when what I really needed to fulfill my creative needs was to be outside and independent."

Pat's creative needs have always served his concern with conservation and the environment. "A lot of my photos wind up in magazines that promote conservation and discuss issues of environmental quality. They promote parks, and preservation of the wetlands." And they get results: "The first book I ever worked on was a conservation book called Washington Wilderness: The Unfinished Work. It was designed to get public and Congressional support to expand the National Wilderness Preservation System. As a lobbying tool it played a role in expanding the wilderness system in Washington State by over one million acres."

Pat is currently working on two conservation-related projects. One deals with attempts to establish an international park that encompasses regions of northwestern Alaska and northeastern Russia; the second is a book on the cultural and natural history of the country of Georgia.

"Both of these projects are interesting and fulfilling because they've been cultural experiences for me," Pat says. "I was in Russia shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union. I was on a two-week trip in a walrus-skin boat following the coastline of the Bering Sea, a landscape that was totally new to me.

"The international-park proposal includes four existing national-park areas in Alaska, where wildlife has played such an important role in the culture. In my work outside of that region there's not much emphasis on wildlife and native people, so the work is fulfilling to me also because I was photographing subjects I don't normally photograph."

The Georgia project stems from a visit Pat paid to the area when it was a Soviet republic. The collapse of the Soviet Union put the work on hold, but in 1998 Pat once again visited what was now the country of Georgia, renewed friendships and became involved in the effort to produce a book on the 3,000-year-old country's natural history and cultural monuments, with, he says, "a heavy emphasis on environmental efforts."

His photographs of Georgia are a mix of his sharp, precisely composed images and a series of photographs that are also carefully composed but exhibit a decidedly impressionistic look. "You know, I always did the impressionistic views, but I've never been known for them. I've been doing multiple exposures since the mid-70s, and shallow depth-of-field, oblique-angle photographs have always been in my library of images, but the clients I deal with didn't choose to publish those. So I'm less known for them."

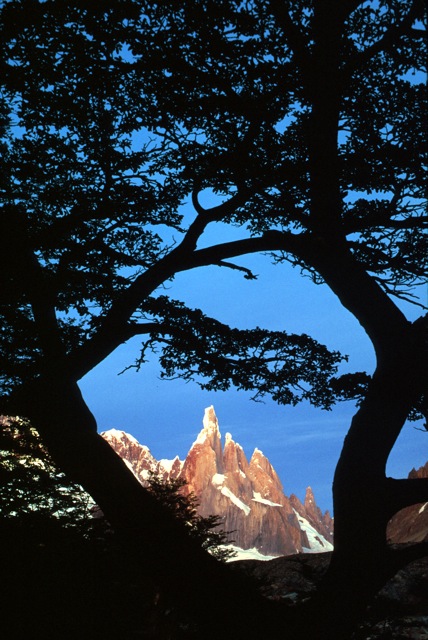

The photographs he is known for are often marked by an extended depth-of-field. "I often compose so the foreground is the emphasis of the photo," Pat says, "and the background acts as a visual complement. When you use wide-angle lenses, the backgrounds always appear so much smaller, so the foreground is always important. I like that because it emphasizes more of the ecosystem. It's an image of the relationship of whatever is in the foreground to the surrounding environment, and, to me, that tells a story about the environment."

Regardless of the stories he's telling, Pat O'Hara will keep shooting in a variety of ways. "I need the variety," he says. "If I were just a landscape photographer doing wide-angle f/64 images, I would have burned out a long time ago."

Pat O'Hara has been an NPS member since 1985.