Rich Clarkson: The Right Place at the Right Time to Get the Shots

Rich Clarkson is a Nikon Legend Behind the Lens

At some point in a long and distinguished career in photography, you get to see your own history coming around to meet you.

Rich Clarkson, acclaimed photojournalist and specialist at capturing not only the peak moments of sports, but the important moments before and after, tells us this story:

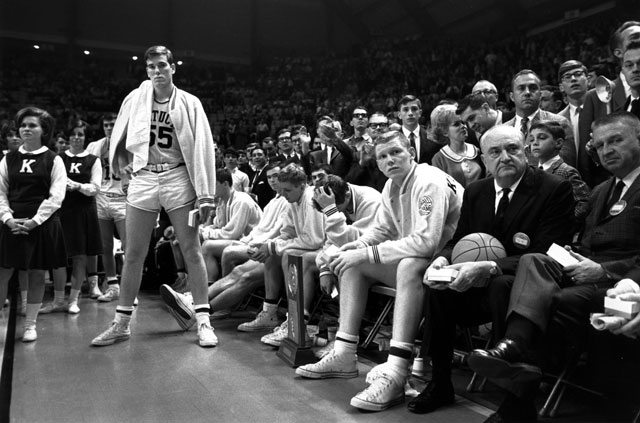

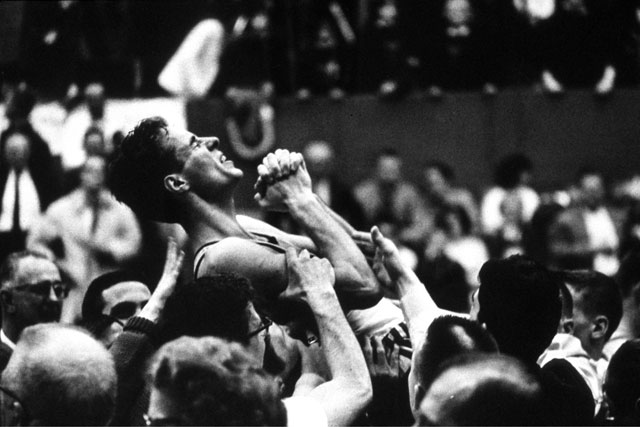

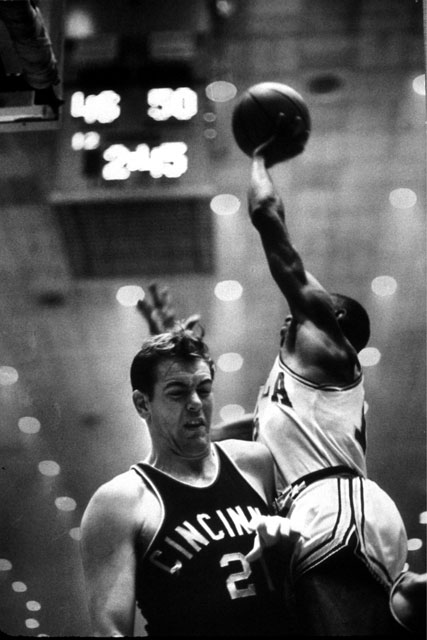

"In 1988, Kansas, my alma mater, was playing for the national NCAA championship, and I was having dinner with a group of friends and a stockbroker from Denver named Rudy Marich, who I'd just met that evening. One of my friends was saying how the 1966 University of Kansas team would have gone to the Final Four and won the national championship except for a terrible call an official made. At the last second, Jo Jo White shot this jumper with Kansas behind by one point. The shot went in, and Kansas would have won instead of Texas Western, and Texas Western went on to win the 1966 national championship, but Kansas was a better team that year. And if it hadn't been for that bad call, Kansas would have been there. And Rudy Marich says, 'Well, it wasn't a bad call. Jo Jo White did step on the line, he was out of bounds, and that's why the basket was disallowed.' And my friend says, 'How would you know?' And Rudy says, 'Because I'm the official who made that call. And what's more, there was some photographer there who took a sequence of pictures that proved I made the right call.'

"And I said, 'That photographer was me.'"

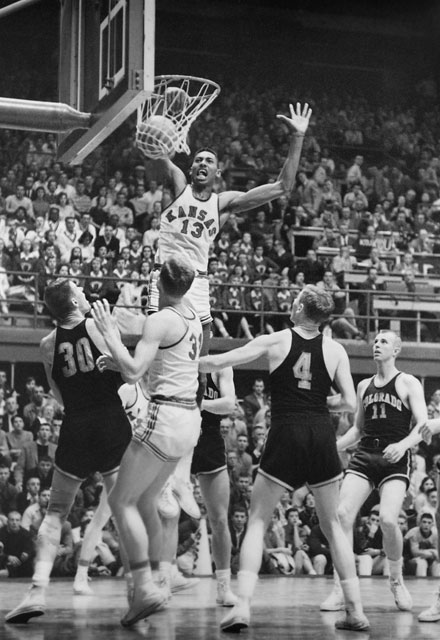

If you look at great sports images of the past 40 years, chances are you'll find that Rich Clarkson was "that photographer" for many of them. And he's still going strong: When we spoke he had just returned from photographing his 48th NCAA championship Final Four round. He covered his first as a freshman in college. Rich was taking pictures when he was in high school, but his first paying job in the business was on the retail side. "I worked in a camera store," he says, "and I took my first pay in equipment—a Nikon SP [a 35mm rangefinder]. While I was in college, I worked for a newspaper in Lawrence, Kansas, and that's where I started to do a lot of sports—and a lot of other things as well. But mostly sports because in a college town, the biggest news is always sports."

In a career that includes magazine and newspaper photojournalism, Rich has been director of photography and senior assistant editor of the National Geographic Society, assistant managing editor of The Denver Post and a contract and contributing photographer to Sports Illustrated. A past president of the National Press Photographers Association, in 1987 he founded his own company, Rich Clarkson & Associates, which currently produces images for a number of projects and clients, including photography for the 93 national championships of the NCAA and all the original photography and publishing for the Colorado Rockies and the Denver Broncos.

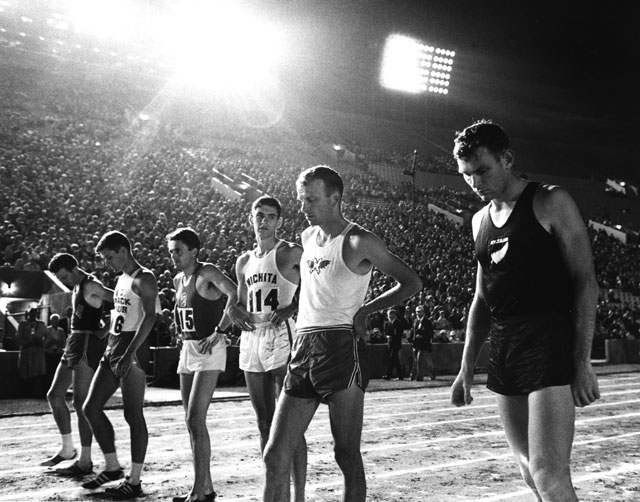

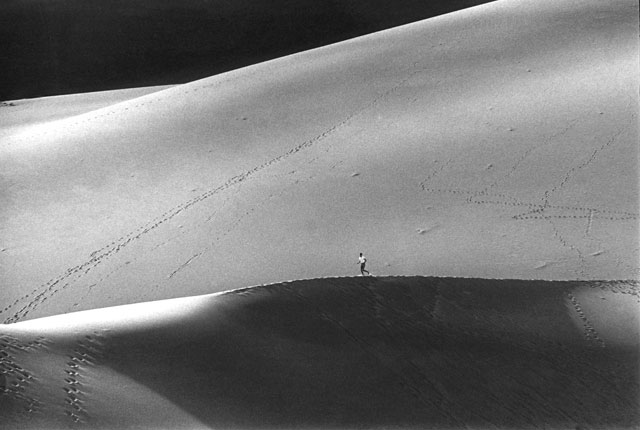

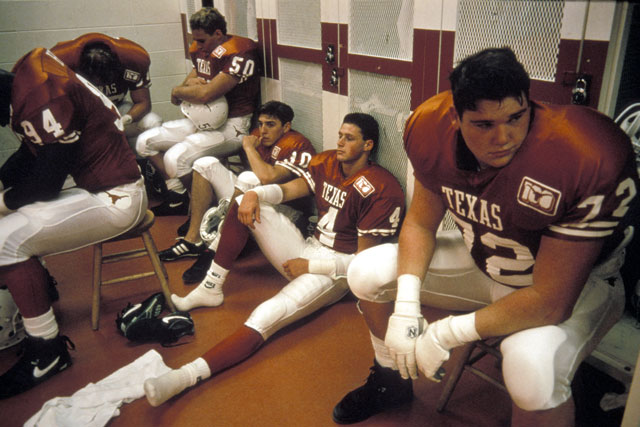

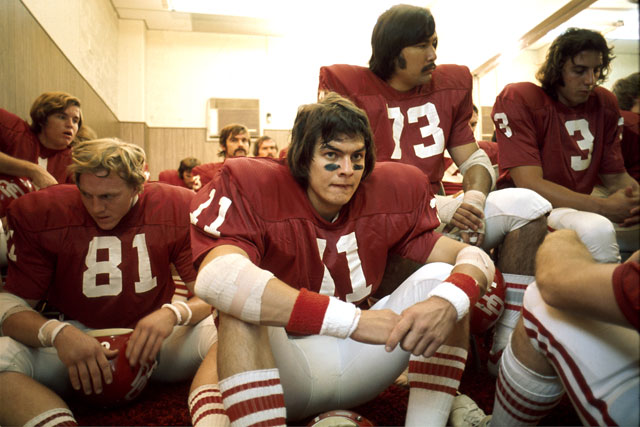

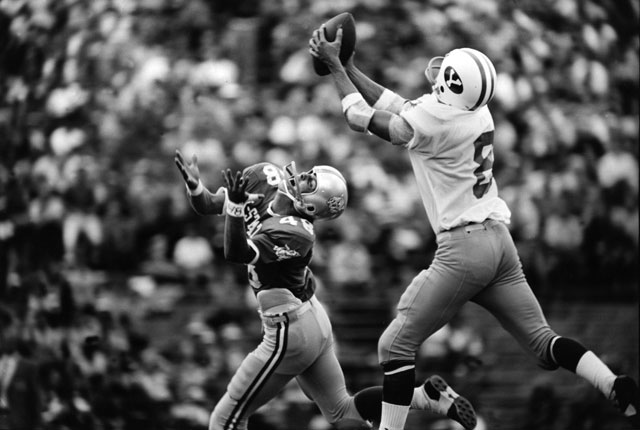

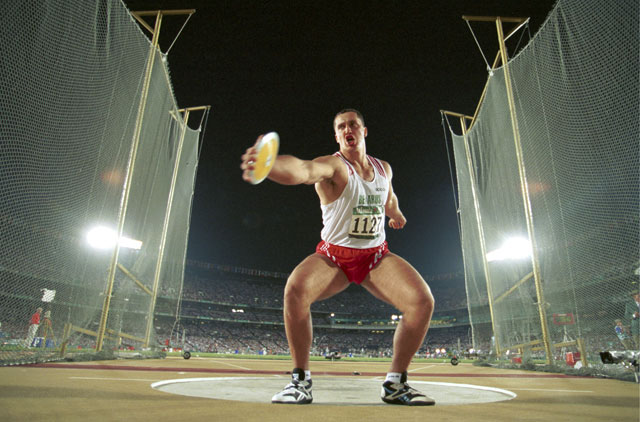

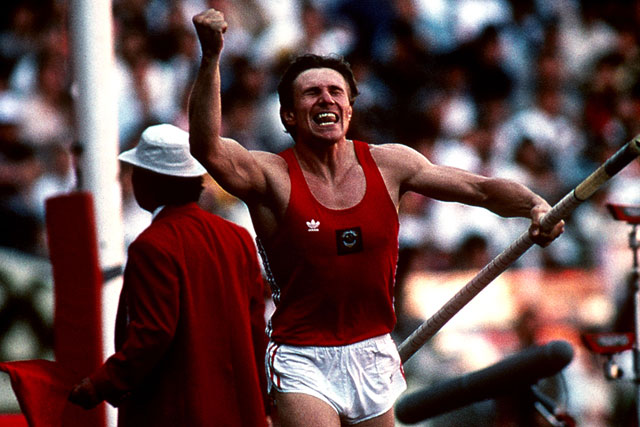

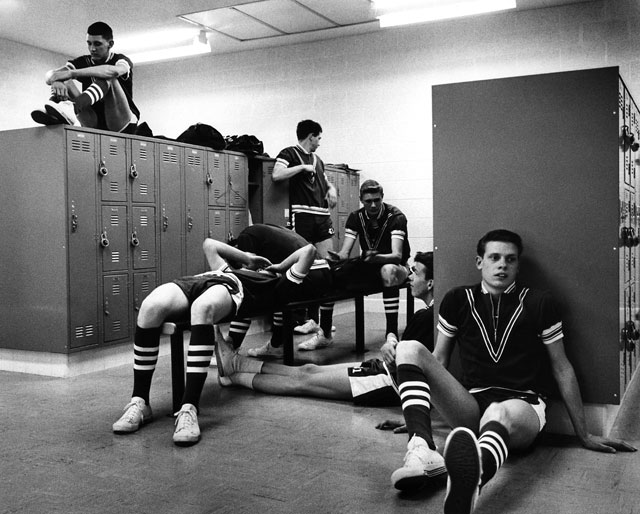

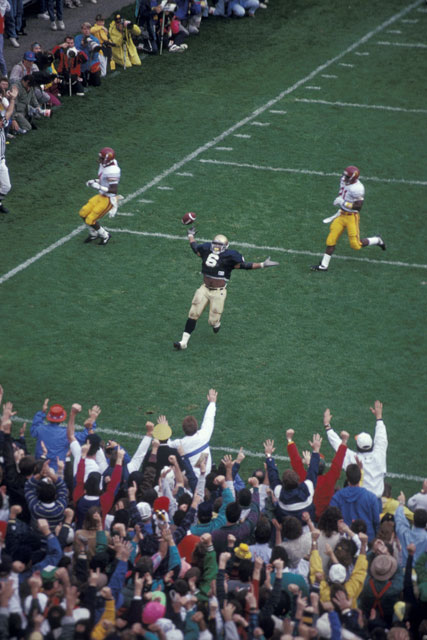

Sports photography is about capturing the peak moment, the turning point of the game. What Rich adds is the sensibility of the photojournalist, the storyteller who also seeks out key moments before and after the contest. He is in the locker room and on the field as preparation takes place. He documents the reactions of the spectators. He's there as runners warm up, divers take their practice leaps and coaches and managers go over plans and deliver pep talks.

"In photojournalism, access is the most important thing," Rich says. "Getting people to allow you to photograph in places and at times that are of great significance, that's important. The significance may be the winning touchdown, but the more significant factor that led to that touchdown or influenced the entire game might have been something that happened at half-time or away from the game itself. So knowing the event and figuring out what's really significant and then trying to make the best possible picture of the most significant elements, that's photojournalism."

Access doesn't automatically mean success, though. "A lot of the best pictures are the result of being around quite a bit before the game," Rich says, "so you kind of blend in. All the players just think of you as 'yeah, there's this photographer and he's been doing this thing, been with us for a week, and we just don't pay attention to him anymore.'"

Sometimes access means putting a remote camera in a room to get the vantage point the photographer can't reach. In the sixth photo you see here, Rich's remote captured coach Lou Holtz addressing his Notre Dame players. "I did a whole season with Notre Dame," Rich says, "So I got to know everyone. Holtz was good about the whole thing. That picture was made with a remote camera attached to the ceiling. From that same camera position I had a whole series of pictures: On the night before the game, there were students in the room painting the helmets gold, which they do before every home game; then the players stretching and taping up; then Holtz speaking to them; then all of them kneeling in prayer. The camera was up there because it's a small locker room, and I just couldn't get that position unless I stood on a ladder, and that would have been disruptive."

Not only did the players get so used to the camera that they ignored it, they also ignored the lighting Rich had to add. "There were greenish fluorescent lights, and I had to hang some 3200-degree Kelvin lights to balance the lighting for the film. The trick of it was to go in and put those lights up the day before and let all the players get used to that different light level."

You might think that access like that is reserved for professional photographers, but Rich will tell you that an amateur can often do even better. "For a Little League game or a soccer match, an avid amateur shooter has better access than anyone covering the Super Bowl, the World Series or a Final Four. You can get really close. People are not going to be that concerned about someone being around with a camera. There are no ropes to stand behind. And in a lot of instances you may know some of the players, so you know their tendencies and how they might react, so you can anticipate what might happen. Shooting amateur sports, you have real opportunity to make great pictures."

Part of Rich's work these days is teaching aspiring pros—and pros who are looking to get better. His company conducts two workshops, Photography at the Summit and the Sports Photography Workshop. The former is devoted to digital photography, the latter combines film and digital. Rich is enthusiastic about digital imaging, especially as a teaching tool. "As a teaching medium, digital photography is amazing," he says. "You've got the picture to look at an instant after you take it. So last year for both the sports and the summit workshops, we had digital cameras plugged into laptop computers. We had a couple of sessions about lighting, and we'd shoot a picture and there it is, and then we could show all the students the effect of changing the lighting—if we move this soft box closer, you see how the light surrounds? Move it back and see how you get more shadows? It was amazing."

It's likely that some of the students Rich is teaching today will be photographing with him tomorrow. History has a way of coming around.

"About 25 years ago I was working on a photo essay on Little League for Sports Illustrated," Rich says. "I followed the Johnson County [Kansas] league for a week, and there was one kid who was the perfect freckle-faced, all-American, eight-year-old Little Leaguer. One of my pictures of him was a key picture in the photo essay.

"Years later I'm using a couple of seniors at the University of Kansas as assistants on some work I was doing. One was Jim Gund, who ended up being a contract photographer at Sports Illustrated. The other was a kid named Mark Winkelman, who's now a state official in Arizona. One day Mark told me that when he was a little kid there was some Sports Illustrated photographer who took a really good picture of him. Up until then I hadn't recognized him. I took a good close look and said, 'That was me!'"

|

Rich Clarkson has been an NPS member since 1973. |