Over-the-Top Underwater Photo Op: The Irresistible Lure of Sharks, Seals, Sea Birds, Dolphins and Billions of Sardines

They’re called “bait balls”—masses of sardines that attract sharks, dolphins, seals and sea birds during their months-long migration from the southern coast of South Africa, first east, then north along the eastern coast.

Known as the KwaZulu-Natal sardine run, the migration draws photographers from around the world who come to capture underwater still and video images of the billions of sardines and the incredible frenzy of underwater activity that results from their passage.

We recently talked with three photographers who came to the 2023 run, each with her own reason to be there. What they shared was mutual support and encouragement, the undeniable lure of the challenge and an enduring commitment to protect and preserve the natural world.

Each has a story to tell.

Rachel Patterson

“Sometimes they stare a little too long.”

“There’s a lot to look at down there,” Rachel says, “and a lot to be aware of—the depth, the activity, the predators, especially the sharks. They mostly take a look at you and pass by, but sometimes they stare a little too long, and that’s when I’m, Okay, I think I’m gonna leave.”

“A lot of the bait balls kept running toward me and by me, and I was snapping away,” Rachel says. “But they were actually running away from the dolphins and the sharks, and I was kinda trying to run with them.” Z 7, NIKKOR Z 24-70mm f/4 S, 1/60 second, f/4, ISO 100, Programmed auto.

Rachel is scuba certified, but two of her photos here—the sardines and the dolphin—were taken at snorkel depth. “I was mostly on top of the water, but sometimes, depending on what was going on, I’d push down a little bit more and let my snorkel fill with water and hold my breath for a few seconds to get the shot.”

“Getting the shot” was always on her mind because the sardine run marked the first time she’d done underwater photography. It was something she intended to do; it just arrived sooner than expected when Kristi Odom called. “She asked me to come along on the South Africa trip with her,” Rachel says. “We’d met about seven years ago when she started to get into doing workshops. We became friends about that time, and she asked if I wanted to go on a workshop to Alaska to photograph grizzly bears during the salmon run. It would be my first time for going to Alaska, my first time going camping and my first-time photographing wildlife. I was, ‘Sure, that sounds great, and I need to borrow all your camping gear.’”

Following the Alaska adventure was a photo safari to Kenya, after which Rachel had no doubt she was “pretty much hooked” on travel and wildlife. “This time, with South Africa, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as a sardine run, but I said, ‘Okay, and you’re going to send me information on underwater photography and camera housings, right?”

“The dolphins would sometimes hold back, then dart straight into the bait ball. This one was waiting for that moment.” Z 7, NIKKOR Z 24-70mm f/4 S, 1/40 second, f/4, ISO 100, Programmed auto.

The result, of course, is that Rachel pretty quickly added underwater photography to her “hooked on” list. Which is saying something for a photographer whose specialties were wedding, boudoir and lifestyle images. “Oh, I’m still a wedding and boudoir photographer,” she says. “I love doing it, but travel and wildlife is now where my true passion lies. The future? I’ll have to see how it goes.”

“This was a scuba shot; that’s the bottom of the ocean right there. The seals move fast—they would zoom up, stop for a second, look at me, then they’re off. I was shocked I got the picture because of how fast they were.” Z 7, NIKKOR Z 24-70mm f/4 S, 1/400 second, f/10, ISO 640, Programmed auto.

For Rachel, the common factor in her photography is storytelling—“the story of a day, a person, or the story of what animals are like and what they go through interacting with each other”—and it’s storytelling for a very specific purpose. “I’m from a very small town—a town where I still live,” she says, “and I always wanted to travel, and now I’m doing it, and now I love sharing my stories, showing the people here what I’ve seen. I’m constantly asked, ‘Where are you going next?’ I love that I can bring the world of wildlife home to them. I want them to be aware of it, love it as much as I do and protect it.”

There’s also a crossover effect. “I think my wildlife photography has improved my wedding photography. What I learned from Kristi is to find emotion in wildlife photography, to find a connection with the animals. I bring that back not only to my town, but to my wedding photography. Now I look for emotion in both worlds.”

Kristi Odom

“Everything moves incredibly fast, all the time.”

“What’s important in photography is passion,” Kristi says, and that especially applies to her wildlife photography, which she hopes will connect people emotionally to wildlife so they too will care about protecting it. But a year or so ago, she hit a rut. “I felt there was so little of me in my images, and I wondered how, without emotion in my work, could I ever create a connection?”

So she went back to the beginning. “When I was young, I used to go on diving trips with my dad. The second I went underwater, the world I knew disappeared. All of a sudden the sublime was all around me, and I knew I had to have a camera. That was the start of my career as a wildlife photographer.”

She thought of the sardine run, something she’d always wanted to see. She made some calls and connections, and soon other photographers began to become part of her journey—first Rachel Patterson, and then Zandile Ndhlovu, who lives in South Africa and had experience with the salmon run. “Zandi helped Rachel and me prepare for the run. She gave us a lot of advice and support, and it turned out the three of us shared a vision for bringing a love of the ocean to others.”

A humpback whale’s tail as the light caught the thrashing of the water. “I was photographing dolphins when the whale came up to me. I would never approach wildlife that closely.” Like the other square-format images here, Kristi cropped this photo from a horizontal to emphasize the essential story elements. Z 9, NIKKOR Z 14-30mm f/4 S, 1/800 second, f/10, ISO 1000, manual exposure.

Photographing the sardine run means you’re surrounded by subject matter, all of it in constant motion, all with one of two goals: eat or avoid being eaten. “The sardine run creates a feeding frenzy,” Kristi says. “Everything moves incredibly fast, all the time, and you have to stay alert.” Most of her photos were taken while snorkeling. “Everything about the sardine run was new to me, and mostly hovering on the surface kept things as simple as I could.”

Kristi’s first underwater camera was Nikon’s Nikonos, a specialty film camera made for underwater photography. Film meant 36 exposures, then surface to reload, and camera technology at the time meant no autofocus. Digital and waterproof housings changed everything. “Now I can get thousands of shots underwater with a pair of CFexpress cards,” Kristi says, “and I can totally rely on the Z 9’s AF system. I’m usually a wide-area autofocus person, but because things on the sardine run were happening so fast, I didn’t want to toggle the wide-area box, so I went pure 3D AF tracking. And along with the Z 9 and my NIKKOR lenses, I went top-of-the-line for the underwater housing.”

“I’m drawn to shapes in my photography, and this came together with the beautiful light in the center. For me the thing with dolphins is how they work and communicate. It seemed they moved together to gather and feed. There were definitely organized patterns.” Z 9, NIKKOR Z 14-30mm f/4 S, 1/800 second, f/8, ISO 1600, manual exposure.

“Seals were swimming where the water was crashing against rocks, creating foam-flash textures that looked like lightning from below.” Z 9, NIKKOR Z 14-30mm f/4 S, 1/400 second, f/18, ISO 640, manual exposure.

There’s no doubt that Kristi’s passion for photography has been reignited. “I learned a lot last year,” she says. “There was a moment when I noticed that before getting in the water, Zandi put her hands together, then put them on her heart. I asked her why she did that, and she said, ‘I take a moment of gratitude, before and after. I'm so lucky to be able to witness this beauty.’ I thought, With all the time I spent in nature, when have I given myself time to feel gratitude before and after? I have those moments now. It wasn’t just the sardine run, or any wildlife that I needed to help me feel my passion again. It was people.”

Zandile Ndhlovu

“Stories link to the human need to know more.”

“When I started shooting underwater, I wanted to shoot video,” Zandi says, "but I knew that in a world that consumes content so quickly, still photographs give us images that can open up the world and allow us to tell a story. And stories link to the human need to know more. That’s how you can create societal change—you get to elaborate on the stories after the pictures have done their attention-getting jobs.

“And we can also go back and revisit a place, maybe five years later, and take a different photo, and be able to say, ‘This is what has happened.’ So in that way stills move a bit slower than videos, but I feel they have more impact.”

“Our boat was about 75 meters away from the whale. We never get too close; we don’t know how many are breaching or from where. For me this picture is powerful because South Africa used to do whaling, and once it was banned the humpback whale populations came back. I believe it’s a story of hope, of what can happen when we make a change.” Z 30, NIKKOR Z 70-200mm f/2.8 VR S, 1/2000 second, f/5.6, ISO 640, manual exposure, Center-weighted metering.

“This one is special for me because it shows the raw coastline and the contrast of how close we are to land but how far the people on the land will be from the beauty that lives in the ocean.” Z 30, NIKKOR Z 70-200mm f/2.8 VR S, 1/1250 second, f/5.6, ISO 125, manual exposure.

Zandi is an experienced scuba diver and free diver, and in 2020 she established the Black Mermaid Foundation, which introduces snorkeling to kids in ocean-facing communities. Under her guidance and encouragement the group aims to banish fear and replace it with familiarity, to make a connection that eventually leads to protection of the ocean.

She is also South Africa's first Black free-diving coach, and she’s free-dived several sardine runs. Free diving is diving with no equipment other than a mask and fins. It’s hold your breath, swim down and, in Zandi’s case, take in the wonder and beauty of the ocean as she takes pictures.

“I often compare a sardine run to something like the Serengeti, when the wildebeests are running for their lives,” she says. “It’s surreal because the only safe way to observe that kind of predation is underwater, where the laws of nature seem to be respected. When a bait ball is running, let’s say one or two humans get in. Then all the predators hold back until the humans get out; then they begin to attack again. That’s why the sardines will try to hide between the people, because then nothing’s coming for them. So our work is to not disturb nature while we’re in the water. If we get too close, we have to move out and allow nature her course.”

“A bait ball, maybe seven meters [about 23 feet] below the surface. If you look to the upper left, that hole was created by a shark that entered or exited through the shoal.” Z 6II, NIKKOR Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S, 1/1250 second, f/2.8, ISO 2000, manual exposure, Center-weighted metering.

Which reminds us that the sardine run is ultimately far more than a photography opportunity. It’s a primal force and practice of nature. “We’re not the preferred prey of sharks,” Zandi says, “but that doesn’t mean you are ever not aware of your surroundings. You are witnessing and photographing incredible moments, but that doesn’t mean you can forget you are in the wild.”

And if you momentarily forget, the nature of a bait ball will remind you.

“To come across a shoal of sardines that thick is insane,” Zandi explains. “They close you in and you wonder why it’s gone dark, and you look up and see you’re covered by this ball. You realize you have to surface because if a shark finds you inside the bait ball—that’s just not a good look.”

For Zandi free diving is “access to a beautiful world,” and just how much access depends on your level of training. Zandi’s deepest dive was 35 meters (about 115 feet); her longest breath hold, four minutes, 45 seconds.

It’s an incredible feeling, she says, but it comes with the need for incredible discipline. “What you’re doing is teaching your body to be able to function at high levels of carbon dioxide. Ultimately your body will ask to breathe, but you can’t take that breath. So much about free diving is about discipline, about not letting your body take over, of being aware of your surroundings, and aware of your abilities—and knowing there’s never any need to push past them.”

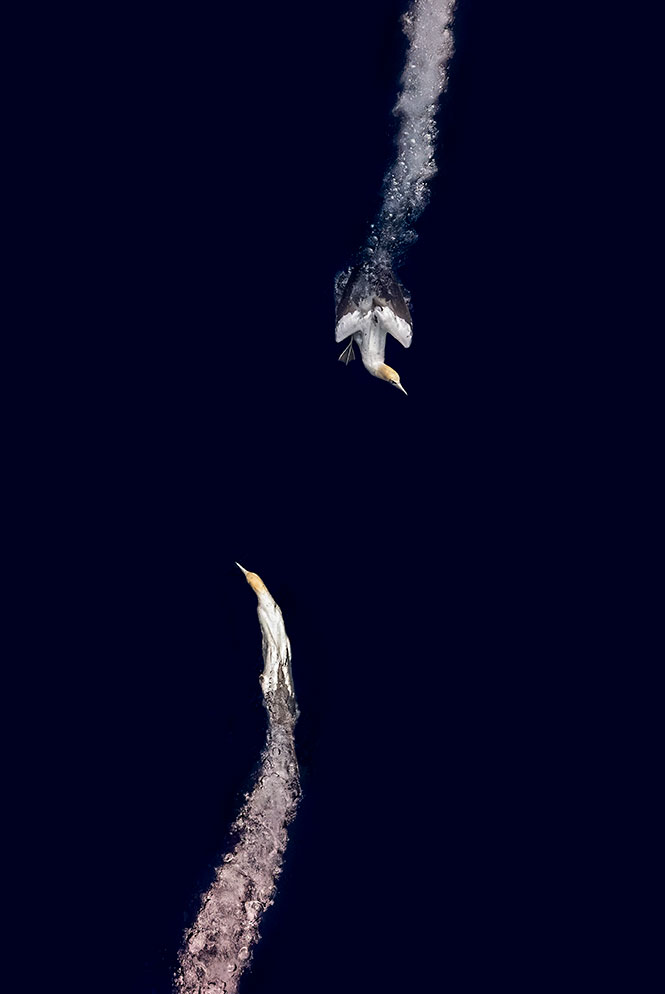

Zandi got this image from her position above a shark whose passage formed a channel between the sardines. Z 6II, NIKKOR Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S, 1/1250 second, f/2.8, ISO 2000, manual exposure, Center-weighted metering.

Zandi’s efforts are concerned ultimately with the relationship of people to the environment; the ocean in particular. “I think that people can only care for something that they feel they have a stakeholdership in, and for a large part of the global majority the ocean has been a fearful place. We have to keep on telling our story until people begin to see that the ocean is not separate from them.”

A key part of her work is emphasizing that all people belong in and around nature. “The question is, Can I tell a story that invites someone to care? Can we make that change, make that happen? We show the sharks, the dolphins, the humpback whales, and someone begins to wonder about a world they’ve never seen—and here’s this Black girl, doing it over and over again. And just maybe, it lands.”

Rachel Patterson, Kristi Odom and Zandile Ndhlovu. In the background are the rock formations that produced the lightning-like flashes of foam in Kristi’s seal photograph.