Imagine That

Joe McNally is a Nikon Legend Beind the Lens

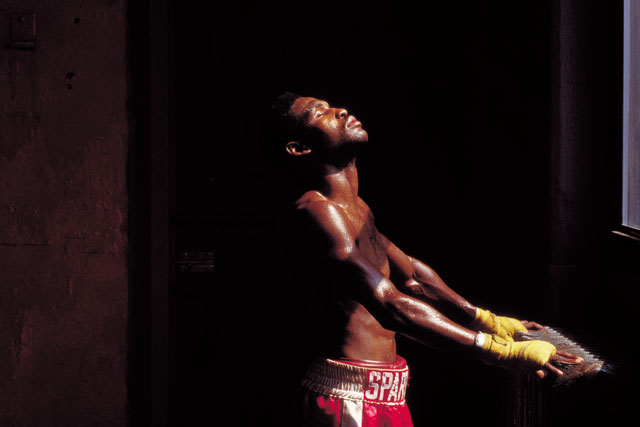

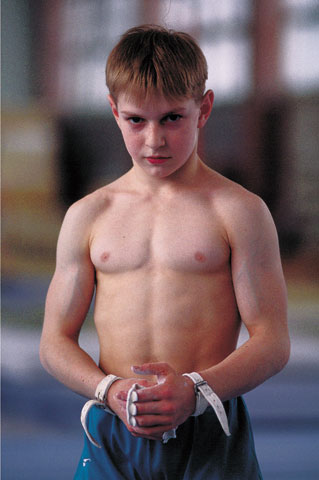

Capable of going from the operating room to the sports arena to the cockpit of a jet aircraft, Joe is the very definition of versatility.

So, how do you grow up to be Joe McNally?

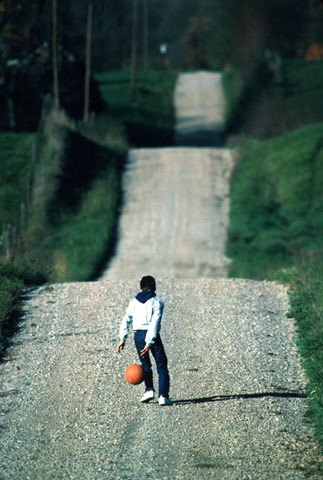

You don't grow up with photography. Rather, you go to Syracuse University and enroll in the journalism program with the idea of being of a writer, specifically a sports writer. Then in your junior year you're required to take a photography course. And everything changes. “Once I seriously took a camera in my hands,” Joe says, he knew that being a photographer was “what I was cut out to do.”

After college the only job he could land that was anywhere close to photography was as a copy boy at the New York Daily News, where he got to hang out with some great photographers. After that it was a stint as a stringer for the wire services, The New York Times and The Philadelphia Enquirer.

In 1979 Joe joined ABC Television as a staff photographer, a job he quit when Discover magazine offered him an assignment to photograph the launch and landing of the first Space Shuttle. Although it was only a three-week freelance job, Joe saw it as the start of a freelance career and easily gave up his steady gig at ABC.

He'd made the right choice. What followed were assignments for Life, Newsweek, Time, Sports Illustrated (where he was a contract photographer for six years), Fortune and National Geographic. In 1995 he was named staff photographer at Life, becoming the first person to hold that post in over 20 years. Joe has won several journalism awards, including the Alfred Eisenstaedt Award for outstanding magazine photography.

Today Joe, who was described by American Photo magazine as “perhaps the most versatile photojournalist working today,” is as sought after for his concepts and ideas as he is for his technical mastery of complex setups.

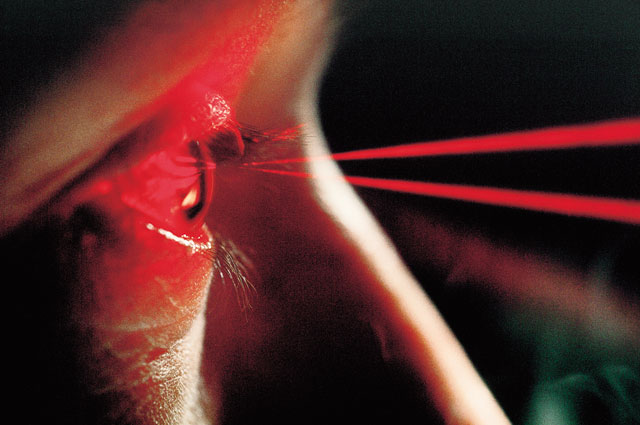

Welcoming all challenges, Joe is a master of not only the camera, but of lighting, too, using everything from SB-28 Speedlights to elaborate studio-strobe setups. And if at first you don't notice the lighting in his photos, then he's really getting it right. “I don't want my lighting drawing attention to itself or overwhelming the scene,” Joe has said. “It should be part of what I'm trying to express. I don't want the lighting to interfere when someone is looking at my photographs.”

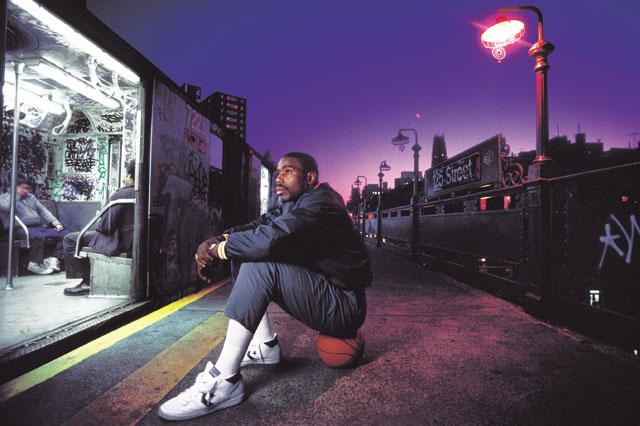

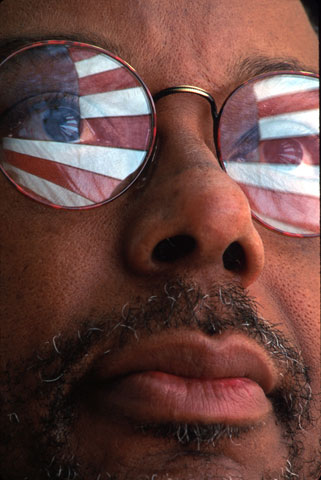

What he wants his photos to do is affect you. “The best photographs move you emotionally, intellectually, spiritually,” Joe has said. “There's almost a visceral reaction to a really striking photograph that communicates on all those levels.”

Give some credit, too, to his research and resources. “Research is crucial to everything I do,” Joe has said. “It makes those few minutes that I'm behind the camera effective. In fact, going into the field and getting behind the camera actually consumes far less of my time than research.”

As for resources, Joe stresses that he is “more than a guy with a camera and an idea,” no matter how good the idea is. “I've been blessed by working for some terrific magazines that are willing to take the risk with me and spend money on an idea which oftentimes is a bit fanciful and comes with no guarantee of success. I also work with fantastic people.” He singles out his producer, Nina Sabo. “She's pulled together the production of some of the biggest shoots we've ever done. She identifies what's required and what the problems are, and she knows how to anticipate and solve them.”

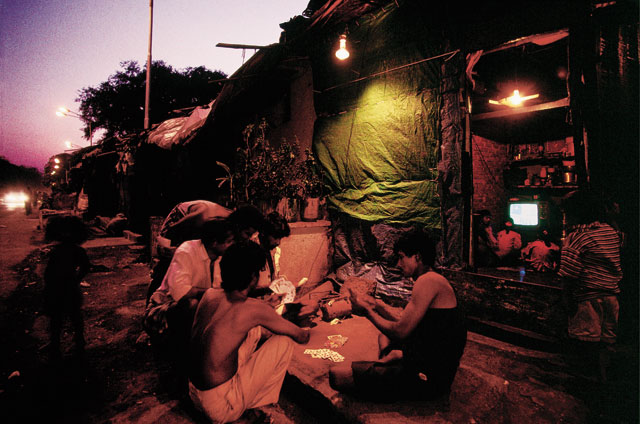

Joe's concepts come into play most often in editorial shoots, where the magazine will pick the theme and Joe can create the concept of the illustration. “Editorially, when they call and assign me, they think I will do it well and they let me have [a lot of freedom in expressing] my ideas. In advertising, the content is more controlled by the client and the art director, but when I work on a concept story for the National Geographic, I basically function not only as a photographer but also as an art director.”

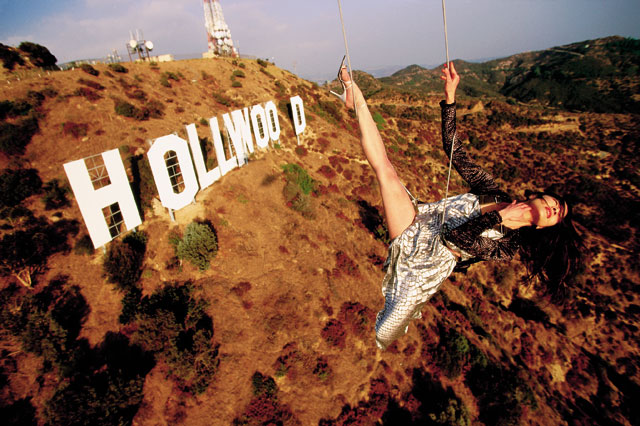

Dangling Shooter, Brilliant Image

The final photograph you see here is indicative of Joe's imagination and the way he likes to work.

“National Geographic was doing a story on global culture,” he says, “looking at the way all of us, worldwide, are trading each other's cultures and having an impact on each other. I wanted to get a shot that symbolized the enormous influence Asian actors and actresses are having on mainstream Hollywood productions.”

Joe got the idea of photographing Michelle Yeoh, of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon fame, in front of the Hollywood sign. But, obviously, not just standing there. “She's a stunt actress, an unbelievable athlete, and what I came up with was the idea of shooting her with the Hollywood sign as she dangled in space from a helicopter.”

Usually that would mean using two helicopters, but, as Joe says, “when you're in one helicopter shooting someone else in another helicopter, you're looking at using telephoto lenses. What I wanted to do was shoot her wide-angle to get the expanse of the Hollywood sign, which meant being very close to her.” And that meant that Joe had to be dangling from the same helicopter as Michelle.

“We got the chief rigger from Titanic and a stunt helicopter group from L.A. We went through yards of FAA approvals—Nina probably made over a hundred phone calls to secure permissions.

“[Michelle and I] were attached by cables to the helicopter, and as the helicopter rose off the pad we simply walked underneath and rose with it. The cables are 20 feet long, so we're both dangling about 20 feet below the skid of the helicopter. Michelle was in an evening gown and began doing stunt-type action moves, and I shot with an 18mm wide-angle lens. She was astonishing in what she was able to do.

“Though it was a simple picture technically—just a straightforward shot in available light—it was an enormously complex picture to come up with in terms of making the concept a reality.”

We wondered about the reaction of the editors at National Geographic when Joe first told them of his idea for the photograph.

“I have such a good relationship with my editor,” he says, “that when I called up and said this is what I want to do, and I'd like your permission to investigate what's possible and find out how much it will cost, he laughed and said, 'Frankly Joe, given your history I'm surprised you're not calling me from the helicopter.'”