Effects of Climate Change on Glaciers Through Time-Lapse

Read the book, see the movie

Six years ago Jim Balog created the Extreme Ice Survey (EIS), a wide-ranging proposal for exploration and documentation that included placing 25 Nikon cameras on glaciers around the world to record time-lapse images that he hoped would capture the effects of climate change on the glaciers.

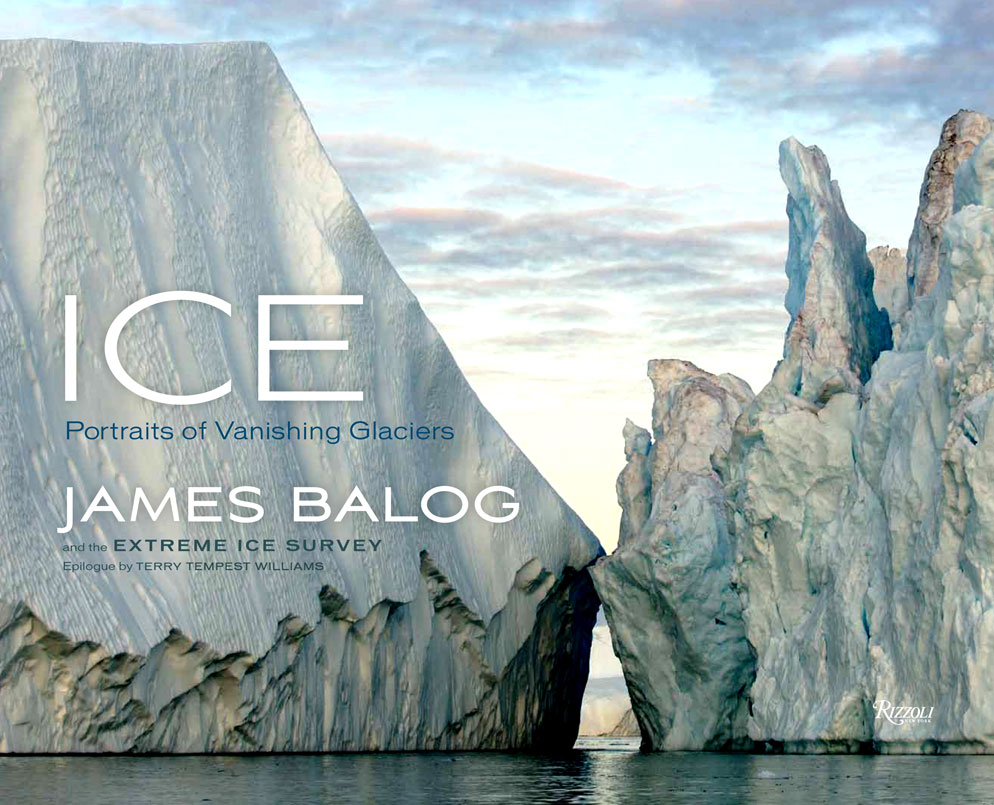

Recently, Jim brought us up to date on the results of his venture: a book, Ice: Portraits of Vanishing Glaciers, was out; a documentary film, Chasing Ice, which chronicles Jim’s initiative and EIS’s efforts, was screened at the PhotoPlus expo in New York City in October, where Jim was a keynote speaker, and have its official US opening in the city in November; and a continuation of the project in the form of a story for National Geographic was under way.

But when I said, “It’s nice when a plan comes together,” Jim just laughed. “Not much of a plan at all,” he said. “It pretty much came together by accident.” Early last year he began assembling the still images he’d taken on the glaciers. “I knew we had a book, and by getting into the editing of the images I was able to see what it might look like. Rizzoli had expressed interest over the years in doing a book on the EIS project, and I called them and told them I was interested, so that was the start of the book.”

The irony is that we have the technological and economic means to make a difference, but what we need is the will and the sensibility.

Ice: Portraits of Vanishing Glaciers, by Jim Balog and the EIS team, was published in September by Rizzoli International.

There had been filming from the beginning of the project. “There was a video crew on the first [still] camera deployment in March of 2007,” Jim says. “I was guessing we had some sort of story here, and I thought we had to have someone with a video camera turned on at the beginning or there would be no way to cinematically narrate it.” As it turned out, it took an editing process that involved viewing 400 hours of film to figure out how to construct the story.

The film is, he says, primarily a narrative about a photographer’s quest to document receding glaciers and the manifestation of climate change. Interspersed are time-lapse images and stills Jim shot throughout the documentation. “At the end of the film what’s revealed through the time-lapse pictures from the fixed-position cameras is how the glaciers are receding,” he says.

The film was submitted to Sundance in September, 2011. “Right before Thanksgiving we got the phone call that we were in, and that was a decisive breakthrough. When you’re a documentary filmmaker you have to score big at Sundance, and if you do, everything else follows.” Chasing Ice had its world premiere at Sundance in January this year, and it took a cinematography award.

The film looks at the technical and weather challenges of the project and the growing awareness that something stunning was happening. “We didn’t realize [the receding of the glaciers] was going to happen this fast,” Jim says, “so in a sense the film is also the story of the EIS team becoming more and more aware of the reality of the way things are.”

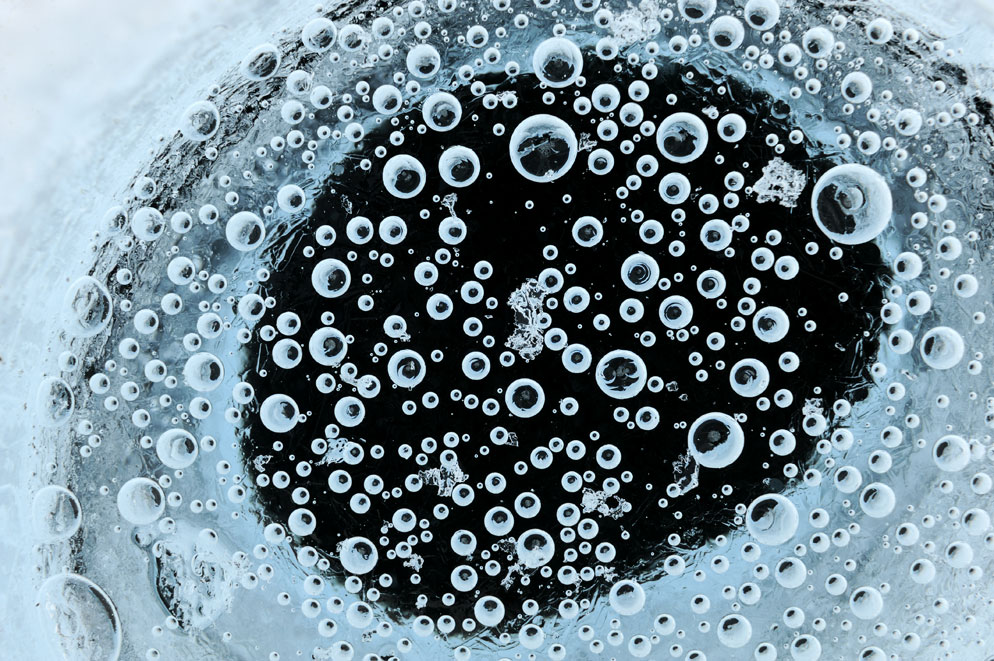

Jim’s images in Ice are incredibly beautiful, but they are exactly what the book’s subtitle says: portraits of vanishing glaciers, the record of a unique landscape rapidly disappearing.

“The irony is that we have the technological and economic means to make a difference,” Jim says, “but what we need is the will and the sensibility. I believe that’s been the missing part of this whole conversation for years. That sensibility is our unique contribution to the social need. We have all this free energy coming down out of the sky, sun and wind that can be used with zero environmental consequences. What we need is a long-term view of the world and its needs. Maybe this book and the film will in some small way throw the gauntlet down: okay, here it is, it’s real, what are you going to do about it?”