Brian Skerry: Below the Surface

Underwater photojournalist Brian Skerry has never been busier. He's been a contributing photographer for National Geographic magazine for over 20 years. "There are a lot of great stories that can come from the sea," he says. "There's so much science and mystery, and reader surveys at the Geographic have continually shown that there is a great interest in these stories."

For the most part these are stories he creates. "A big part of what I do every day is staying in touch with what goes on in the world's oceans." He might be fascinated by a particular species, an ecosystem or a place in the world. "My job is to be regularly in touch with these things and to bring to Geographic good ideas that we can translate photographically."

It's important for people to have a sense of how magnificent our planet is, and that all these creatures live there, and that we need to take care of them.

Brian started out wanting to be an ocean explorer, and he discovered the best way to do that was with a camera. "I loved photojournalism, storytelling with pictures," he says. Early on he just wanted to take beautiful photographs of things that interested him, but the reality of environmental issues changed that. "I saw a lot of problems occurring in our world's oceans and wanted to tell a more complete story."

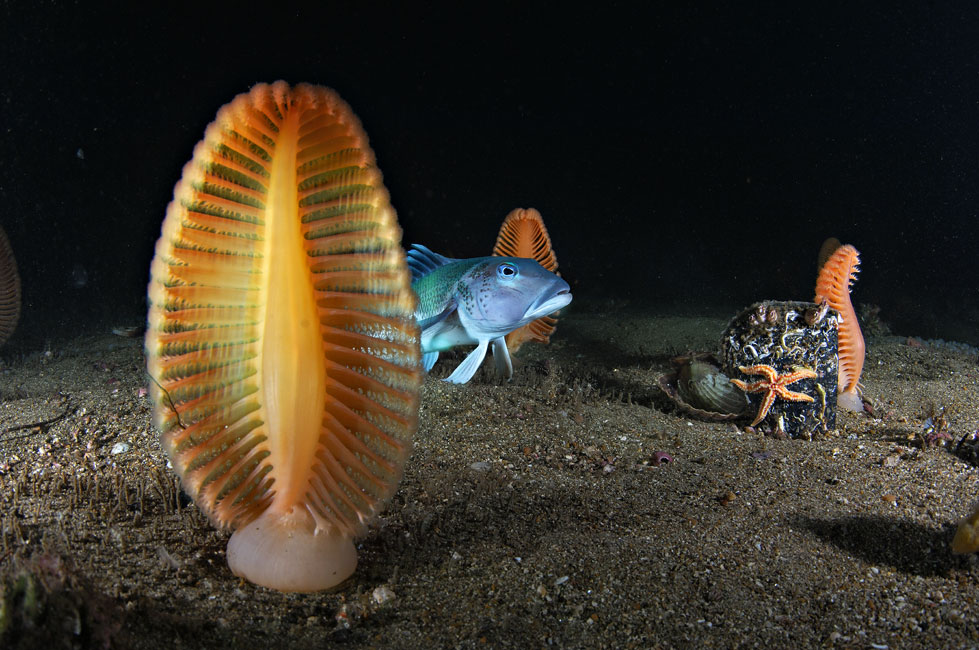

That story is both complex and compelling. Not only do the oceans represent the biggest part of the planet, but ocean plants produce half the word's oxygen. "The ocean controls weather with currents and temperature," Brian says, "and it is also the greatest carbon sink on the planet. Coral reefs, plankton, algae and kelp are turning carbon into oxygen, but the problem is that we are overloading the planet with carbon, and global climatic change is the result of the planet not being able to handle this carbon."

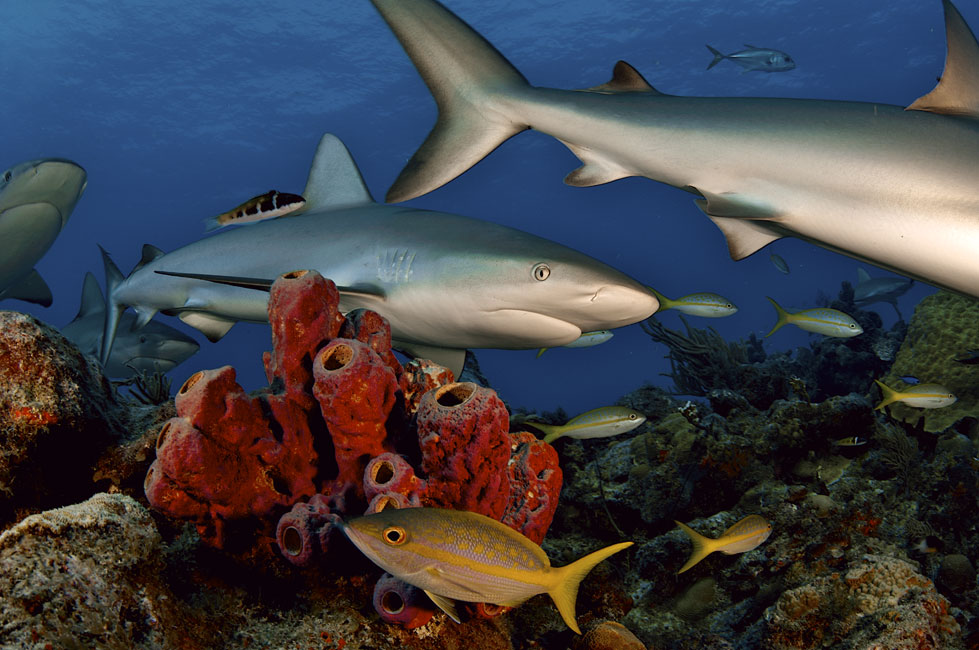

Brian, like other photographers and scientists, cites overfishing as a crucial issue. "Less than two percent of the world's oceans are truly protected," he says. "It's still the wild west, and people around the world can harvest wildlife at amazing rates, rates that are unsustainable. Ninety percent of the big fish in the ocean have disappeared in the last 50 or 60 years. Then you add way too much carbon and you get ocean acidification. The water is turning acidic and the acidification level is killing anything with a calcium base to it—so seashells, mollusks and these little creatures called terrapods, which are baseline food source for so many animals are dying. Rising sea temperatures kill coral reefs as well, so you've got a cascading geometric domino effect. Any healthy eco system is like a Swiss clock with all the little gears meshing to create a healthy environment; everything relies on and is dependent on everything else."

There are steps that can be taken to deal with the problems and Brian's stories also focus on remedies like the creation of more marine protected areas. "For the problems of overfishing we need to have better management," he says. "I have a story coming out next year on aquaculture, showing the latest methods of farming fish around the world that are being used to feed seven billion people.

There are solutions. It's not too late, but we need to take notice."

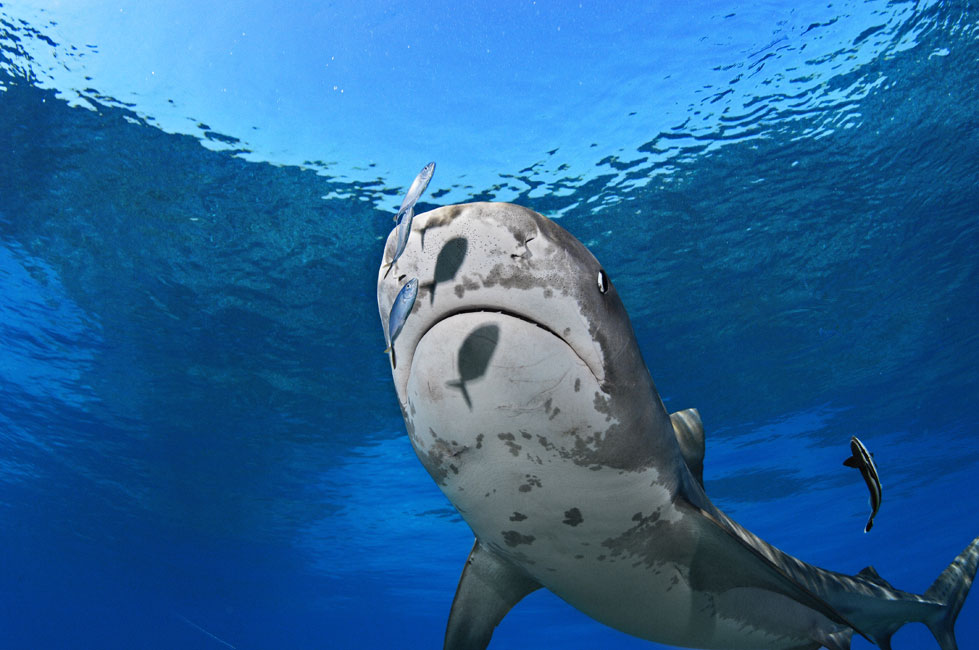

Brian is aware of creating a balance in his stories. "I'm still photographing the beauty of the ocean; my work is still about the celebratory perspective. I want people to fall in love with the ocean and its creatures and their habitats. It's important for people to have a sense of how magnificent our planet is, and that all these creatures live there, and that we need to take care of them."

A school of black margate hover in mid-water off San Pedro Island in Belize. "This was part of my story about the Mesoamerican Reef, the world’s second largest barrier reef system which runs through four countries: Mexico, Belize, Honduras and Guatemala. My story was about the connectivity of marine ecosystems—coral reefs, mangroves and sea grass beds. Each habitat needs the other to survive." D3, AF Micro-NIKKOR 60mm f/2.8D.

Tools of Exploration $

The first camera Brian Skerry owned was a Nikonos II. "I didn't know how to use it, but I taught myself and started making pictures." After studying photography and journalism in college, he worked his way up the Nikonos ladder to the V, then to an F3 in a housing and, ultimately, to digital. The photos here were taken with D2X, D3 and D3S D-SLRs. Brian's been using three D4 cameras since last August. They're encased in Subal underwater housings, and underwater lighting for his images comes from Hartenberger flash units.

He's pretty much a wide-angle prime shooter when it comes to lenses, with an AF NIKKOR 14mm f/2.8D ED, an AF Fisheye-NIKKOR 16mm f/2.8D, and an AF NIKKOR 24mm f/2.8D high on his list of go-to glass. "I started using zoom lenses underwater only a few years ago," he says, "and the bread-and-butter wide angle zoom is the 17-35mm [AF-S Zoom-NIKKOR 17-35mm f/2.8D IF-ED]."