The Edge: Drum Circle

My Own Personal Crüe Fest

I started out shooting rock and roll from the audience, then worked my way to the front of the house, then the photographers’ pit and then onto the stage. What I learned at each access point was this: I could never get a good shot of the drummer. The angles are bad; he’s far back or on a riser; he’s behind a forest of cymbal stands and a fortress of drums—there may have even been a moat or two.

I first tried changing lenses. Instead of bringing a 70-200mm into the pit, I’d put on a 200-400mm with a 1.4 teleconverter, so if I had the right angle, I could zoom in close enough to wait for the drummer’s face to fall within an opening, and then maybe I’d get a lucky shot sometime during the three-song limit under which I worked. I’d accept a lucky shot, of course, but it wasn’t what I wanted. What I wanted were photographs that overcame the limitations; and, frankly, the kinds that musicians would like and respect. In other words, images that would get me greater access.

A few years back I had a breakthrough that came from a drummer’s question: “What do you want to do that’s special?” I tossed back, half-joking, “I’d like to throw a remote camera on your drum kit.” The drummer replied, “What’s a remote camera?” Once we sorted that out—”I lock a camera onto a stand, right up close to you, and fire it from offstage and we get unobstructed views that no one’s ever seen”—I got to work. The result of that shoot was an image that appeared in the Winter, 2010, issue of Nikon World, and in a lot of other places as well.

Our signature image clearly shows Tommy and the drum kit upside down, and a right-side-up audience, with everything perfectly lit. This was taken during the ride-along for the local radio station’s contest winner.

I’ve parlayed that hero shot into access elsewhere, most recently a performance by Mötley Crüe at Nikon at Jones Beach in September last year. For that show, not only did I have extraordinary cooperation from drummer Tommy Lee, his drum techs and the band, I had exactly what I’m always looking for when I make pictures: something different. I’d have remote-camera access to Tommy’s unique roller coaster setup (though, to me, it’s more Ferris wheel than roller coaster), plus the attraction of his look, style, intensity and place in rock and roll history.

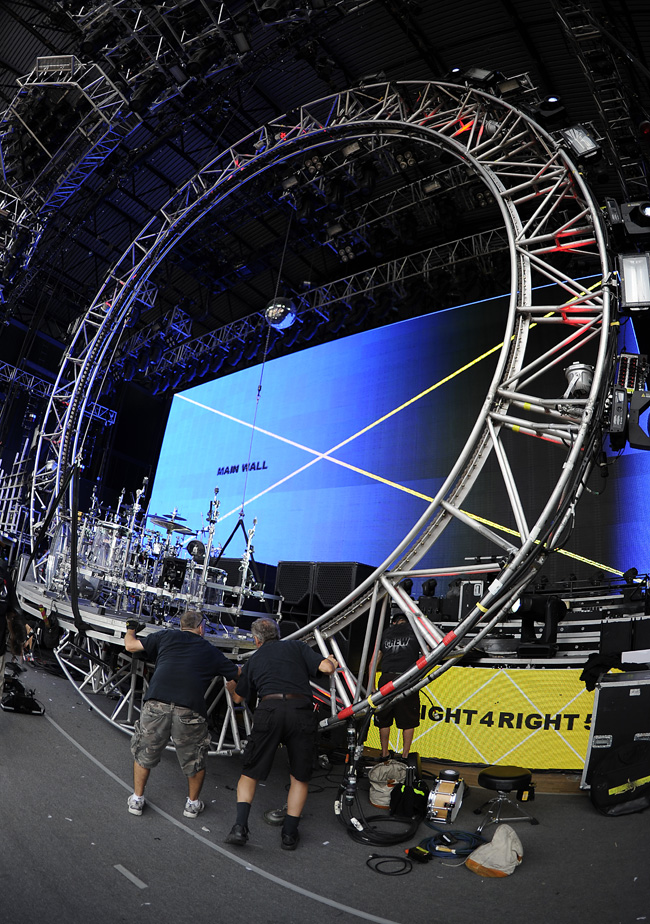

I’d shot Mötley Crüe before, but the wheel was new to me, so I started with online research to get a feel for what it was all about. Okay, a circular track, and at some point he plays completely upside down. Now, let me deal with that opportunity.

I’d shot Mötley Crüe before, but the wheel was new to me, so I started with online research to get a feel for what it was all about. Okay, a circular track, and at some point he plays completely upside down. Now, let me deal with that opportunity.

I took a moment away from setting up the remotes to grab a D3S with its 16mm fisheye and get this shot of the Crüe's crew setting up Tommy's roller coaster drum kit ride.

I made a mental shot list: I’d need an establishing shot; I’d need details and drama and color and mood; I’d need a clean, cool image of Tommy; and for the hero shot, Tommy and the audience—the one stopper that clearly shows that the drummer is upside down. So not only do I have to secure remote cameras to his drum kit, I have to really secure them for the ride around the circle. Right away I’m thinking double safety cables and everything locked tighter than tight.

For the remote shooting I decided on three D3S cameras fitted with AF Fisheye-NIKKOR 16mm f/2.8D lenses and fired via PocketWizard remotes. Two cameras would be on the drum platform and would go with him on the ride, with one aimed to capture clean, cool images, essentially portrait shots, and the other secured to the bottom of the drum kit, aimed up to show how big the wheel was and to get a picture of Tommy upside down. The third camera would be on the wheel itself. I’d be shooting from the front of the house, at the soundboard, with a fourth camera, a D4 with an AF-S NIKKOR 200-400mm f/4G ED VR II and an AF-S Teleconverter TC-14E II.

I could have fired the remotes using a transmitter on the hot shoe of my camera, but with so much to keep track of, I enlisted my colleague, Nikon senior technical manager Steve Heiner, to stand at the side of the stage and fire the drum kit and wheel remotes. Steve knows the band, and he’s got a terrific feel for performance photography. My only instruction to him: shoot, shoot, shoot; shoot some more; don’t stop shooting.

Each remote camera was set for ISO 3200, f/8, aperture priority, -2/3 stop exposure compensation (you’re always afraid of blown-out images) and center-weighted metering. With the 16mm lenses, I was expecting depth of field to Arizona.

Tommy played most of the set with the drum kit’s platform at the six o’clock position, saving the rotations around the wheel for his drum solo and a ride-along when the winner of a local radio station’s contest was strapped into a separate seat and went around the circle with him.

The moment I started breathing normally was at the end of the performance when Steve and I pulled the cameras off the rig, pushed the playback buttons and saw that everything had worked the way it was supposed to. We had pictures, 11,000 of them, and the edit revealed that 90 percent were acceptable and many were downright terrific.

We’d met the challenge of getting great shots of a great drummer, but the challenge is only part of the attraction. Music means a lot to me—it’s truly an important part of my life—and it’s the drummer who sets the tempo. The faster the beat, the faster our hearts race as the adrenalin kicks in; the slower, the more we settle in and relax into the music. So to me the drummer is the star of the show; he’s the heartbeat, and the way he plays keys the emotion of the moment. And we got a great drummer in some dazzling photographs. What could be better?

Only one thing: I could have won the ride-along contest.