The Human Element: James Balog’s Stunning Images of Nature in the Balance

The side of an iceberg that had just flipped over. “This is brand-new, fresh, water-polished ice in the first 45 minutes before the warmth of the air affects it and it becomes frosted.” Jim took the photo in Alaska in 2010 as part of the Mendenhall Glacier melt study.

In 2007, photographer, explorer and conservationist James Balog put 25 cameras, rigged for time-lapse photography, at 16 sites on glaciers in Iceland, Greenland, Alaska and Glacier National Park, Montana. Later, more cameras were added; eventually there were 43 at 24 sites. Some are still there, still taking photographs. His purpose was to dramatically demonstrate that the glaciers were receding, that global warming was real and it was happening right then, right there.

In 2012, his book, Ice: Portraits of Vanishing Glaciers, was published, and Chasing Ice, a film about the glacier study, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and was subsequently screened in more than 175 countries. In connection with the time-lapse study, James founded the Extreme Ice Survey (EIS). He established the Earth Vision Institute, dedicated to an art/science look at environmental change, in 2012.

James recently published The Human Element: A Time Capsule for the Anthropocene, a book that’s essentially an environmental summing up: where we are now, how we got here and what we need to do about it.

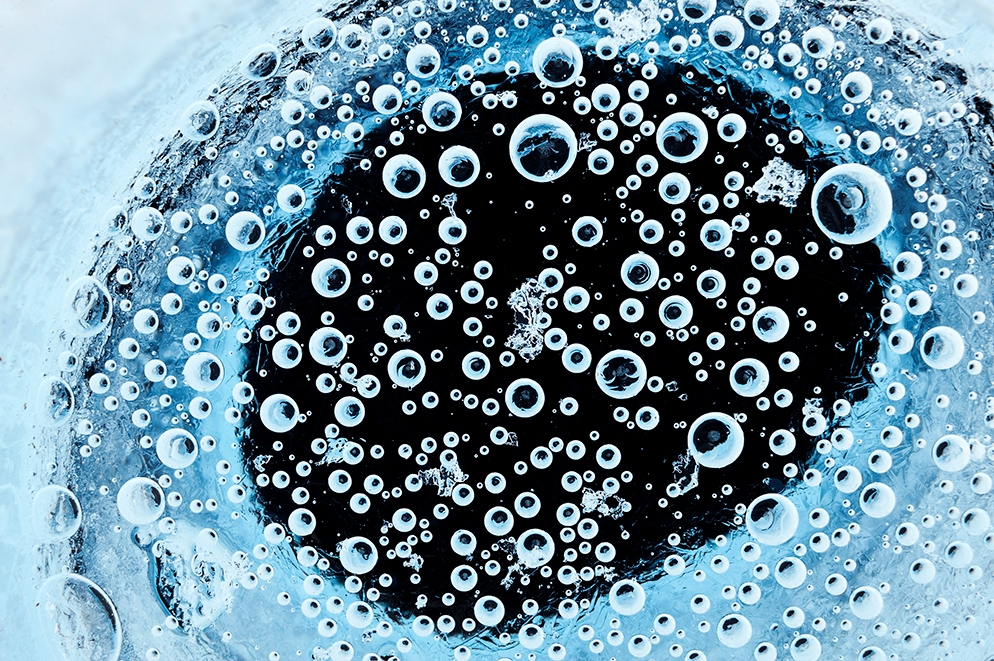

“I’m standing on the Greenland ice sheet, at midnight, looking down at that pool—it’s about ten inches across, and those bubbles are ancient air releasing from the ice sheet as it’s melting. They’re trapped behind a skin of crystal-clear ice that formed as the air temperature dropped and the water froze. The air being released is somewhere between 13,000 and 15,000 years old.”

“We,” of course, is us. We are right there in the subtitle. The Anthropocene is the age in which human activity is the overwhelming influence on climate and the environment. For over 40 years, in photographs, presentations, interviews and articles, James has been conveying irrefutable evidence of environmental change, of how the human element affects the four elements of nature—earth, air, fire and water—and how they in turn affect us. What’s happened at that intersection is the story told in stunning photographs and impassioned text in The Human Element.

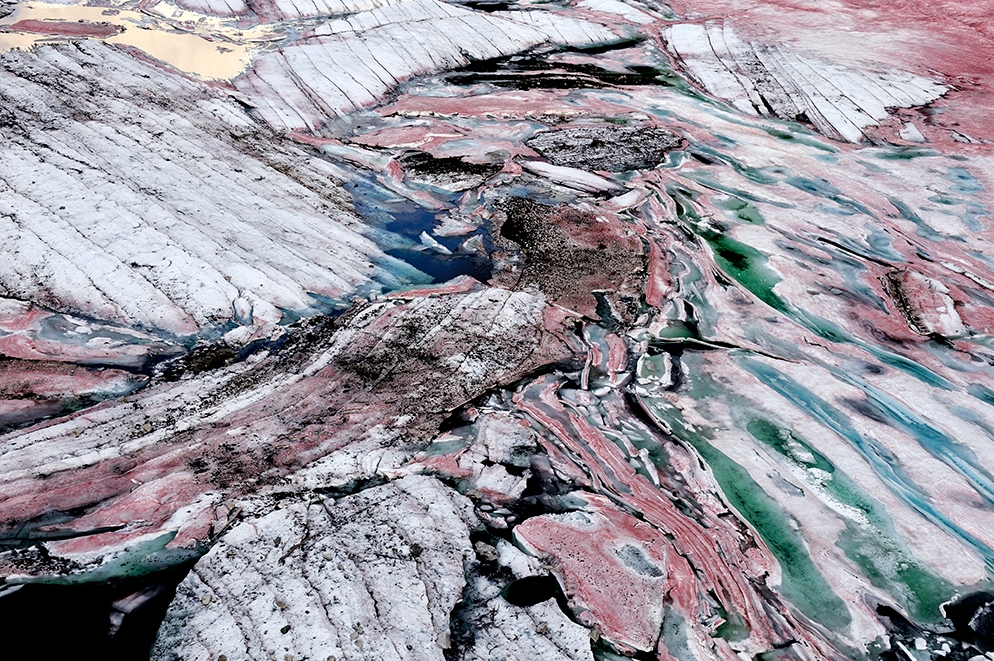

“This was in the Fall of 2008—we were coming back from doing repeat shots of receding glaciers in the Coast Mountains of British Columbia,” Jim says, “and we flew over this unnamed lake and saw this amazing colorful pattern of algae, meltwater and little ice pans mashed together. I couldn’t pass up the opportunity.”

Turning Point

The glacier project began with an assignment from The New Yorker to photograph glaciers in Greenland, which led to a commission from National Geographic to photograph glaciers in six countries. Photographs from that assignment appeared in the June, 2007, issue of the magazine, the cover of which proclaimed “The Big Thaw.”

James was initially skeptical about climate change because he felt that scientists worked their predictions and conclusions from computer models, but his photography on the glaciers was undeniable real-world evidence. He could see changes in glaciers by comparing his own photos to those taken decades earlier. In The Human Element he writes, “Let me explain how and why I changed from being a romantic photographer of scenic nature and outdoor adventure….”

Jim’s daughter, Emily, in 2011, on a beach in Iceland. “That’s the last fragment of an iceberg that broke off from a huge glacier about five miles north. The glacier had been receding and sending icebergs out to sea where they’d get smashed up into smaller pieces, polished by the waves and, on the high tide, thrown up on the beach. Over the years I’ve done studies of these pieces, which I started to call ice diamonds.”

That’s the brilliant concept of the book: to tell his own intersecting, crisscrossing story, a personal narrative of family, heritage, observation and discovery within the larger story of the cause-and-effect link of the five elements.

“When I became a photographer, I wanted to celebrate the elegance and beauty of nature,” he says, but he soon realized there was a bigger, more complex story going on, a story “about the collision between people and nature.” It was a story he began to witness and document, a story that he realized early on was not limited to the elemental forces of earth, air, fire and water. “We’re a force of nature, too. People are changing the other elements, and at the same time those elements are changing us.”

Pahoehoe lava flow, west of Kalapana, on the Big Island, Hawaii, 2013. This image is from the chapter about natural tectonics, Jim’s all-encompassing term for the natural, potent forces of the environment, which sets up the chapter on human tectonics, the damaging forces we bring to the natural elements.

The Book

The Human Element features photos from James’s long career, photographs taken to investigate, document, alert and persuade. There are images of altered earth, of fire, of the results of rising seas and warming oceans, of the aftermath of floods and hurricanes. “Human enterprise is based on the belief that we are more or less able to know what the future holds for us,” James says. “Summers will be hot, winters will be cold, the land will be here, the ocean will be over there. But when those basic expectations change, it throws everything into disarray.”

Controlled burn—more formally, an experimental prescribed research burn—near Fort Providence, Canada, 2015. “They were burning out a section of the forest trying to control the potential for future fires.”

The book is a record of actions and reactions. “Truth matters,” James writes in the introduction. “Evidence matters. The truth of our 21st-century environment, based on unmistakable and irrefutable evidence, is that human needs, behaviors, and technology are radically changing the nature of nature.” The photographs depict the changes we bring to nature and nature’s response, which in effect makes us first perpetrators, then victims. The story demands that kind of blunt impact.

You scan a page, a sentence jumps out: "In ice is the memory of our world.”

Elsewhere, a paragraph: “Against the tyranny of denial and the oppression of indifference we must prevail to find a new vision of the relationship between human nature and the rest of nature.” In a chapter titled Time Capsule, James writes, “We see you, children of the long-arcing future…” and asks, “Do we leave you storms of ruin and a sinking Atlantis, or will you judge us the heroes of a miracle?”

You stop reading for a long moment to think, to absorb. It’s that kind of book.

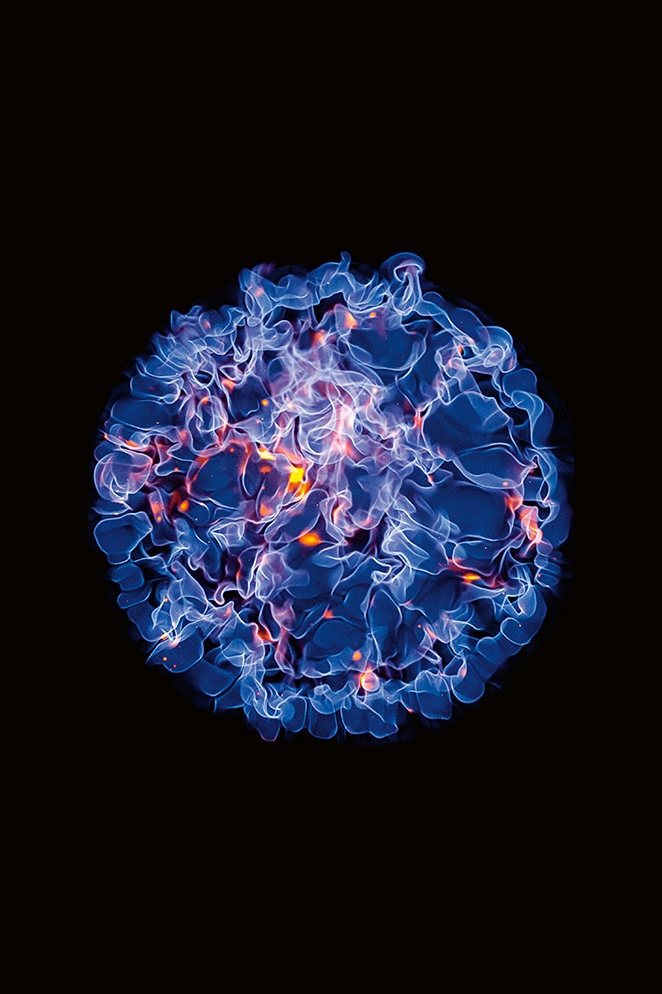

“I went to the [United States Fire Service] Fire Sciences Laboratory in Missoula, Montana, to do studies of fire as a form and a color,” Jim says. “You’re looking down on a methanol fire contained in a large pan. You could call it a symbolic evocation of the world on fire.”

Melted caution lights—the ones that blink when children are getting on and off the bus—after the Fourmile Canyon Fire, in Boulder, Colorado, September 2010.

Eyewitness

Despite round-the-clock, across-the-calendar news, the obvious truth can still be a hard message to deliver, one that people avoid if they’re not directly involved, if the event, the immediate danger or process of change is not having a proximate effect.

“Out there, on the cutting edge of these events—that’s not where most people live,” James says. “But when you’re there, whether it’s fires or floods or children with asthma, the people on that edge experience a distilled, intensified reality that the average person doesn’t, and it takes a long time for awareness of what the edge is experiencing to migrate back into the general population.”

Sometimes it doesn’t make it back at all, or if does, often only a few take notice. “Sunny-day flooding” is now normal in a city on the east coast of America. Chesapeake Bay will, maybe in 25, maybe in 50 years, take Tangier Island, Virginia. Raging wildfires in high humidity conditions elicit a “we’ve never seen that before” response from a firefighter.

In January, 2005, photographed in Banda Aceh after the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, December 26, 2004. “I was in the rubble of the building when this elephant came out of nowhere and started walking into the ruins. It turned out it had been brought down from the logging camps, where they use elephants to carry fallen logs, to help clear the rubble so they could look for victims. I shoot these [two-image] pieces for a real-world expression of how my eye is moving around a scene.”

The story James tells in The Human Element is made all the more compelling by his care not to sensationalize, to present a reasoned, realistic assessment. “The basic premise of [most] environmental thinking is that humanity is one state of being and nature is another…and it was always, Humanity is over here and nature is over there. That’s a dead end, especially in our time. It’s important to realize that humanity and nature are not separate. We are an integral force within nature, and only by recognizing that will we have an authentic chance of saving ourselves.”

It’s entirely possible that we cannot solve the problems we’ve created and/or ignored, but if we accept the responsibility to act, we can mitigate their effect and adapt to their consequences.

Or maybe do better than that. “We are the only element that can restore balance,” James says.

Restore. It’s a hopeful word.